Death and

Transfiguration …Almost

August 8th,

1999

Lying on the ground, writhing in agony

as I desperately fought death and tried to take a breath, I

wasn't thinking about my latest project. I wasn't thinking about

climbing at all. I was thinking about my two boys, Daniel (4) and

Derek (1.5) and that I'd never see them again. I gurgled sounds

as I pleaded with my eyes for the Loobster to save me. I wanted

to say my boys' names, but I couldn't speak. Instead I died.

Or so I thought. I came to about 30 seconds later

as if awakening from a dream. My breathing wasn't uncontrolled

gasps, but measured draws. The Loobster was hovering over me in

an agitated state. I was in pain and knew I had just fallen a

considerable distance onto my back. "How bad am I?" I

asked the Loobster, expecting his response to be "Not too

good, Bill. You've lost a leg, your head is cracked open, and

your bleeding profusely from your back." I forgot his

response, but I soon knew I wasn't bleeding. Initially my most

intense pain was in hands and arms. They had stinging rope burns

on them. I was slumped on my side and so afraid to move. I knew I

had a back injury and cautiously tried to move and feel my feet.

They worked.

Or so I thought. I came to about 30 seconds later

as if awakening from a dream. My breathing wasn't uncontrolled

gasps, but measured draws. The Loobster was hovering over me in

an agitated state. I was in pain and knew I had just fallen a

considerable distance onto my back. "How bad am I?" I

asked the Loobster, expecting his response to be "Not too

good, Bill. You've lost a leg, your head is cracked open, and

your bleeding profusely from your back." I forgot his

response, but I soon knew I wasn't bleeding. Initially my most

intense pain was in hands and arms. They had stinging rope burns

on them. I was slumped on my side and so afraid to move. I knew I

had a back injury and cautiously tried to move and feel my feet.

They worked.

The Loobster was frantically putting his

shoes on and saying, "Oh god, Bill, oh god. I've got to get

help. I'm going for help. Hang in there." Before a few

minutes had passed I was alone.

How could things have gone so wrong so

fast? I thought about my wife and kids. I wondered if I'd ever be

able to climb again. I knew help was on the way. There is no one

I'd rather count on when in trouble than the Loobster. I knew

he'd do what's necessary. I just tried to not to move for fear

that I'd do permanent spinal damage.

The Loobster had arrived only two days

ago from Santa Clara, California. He had immediately gone up and

climbed the Casual Route on the Diamond the previous day. That's

a pretty amazing feat for anyone to pull off: sea level to 14,000+

feet via the 5.10 climbing on the sheer east wall Long's Peak. I

wasn't his partner. He went with Hardly Manson. Loobster was out

for a week of musical climbing partners and Sunday was my day.

Dr. Offwidth, AKA my Armchair Trainer,

had been pressuring me to hike up to Green Mountain Pinnacle near

the Fourth Flatiron and give "Death and Transfiguration"

a go. This was an overhanging endurance climb. The type of butt-kicking

experience which the Doctor relished and I was trying to master.

I had been on this climb only once before: on the safe end while

following the Doctor himself. I had been thoroughly humiliated

and fell off it numerous times. At one point I was dangling in

space and only barely made it back onto the climb after many

minutes of futile swinging.

D&T is a famous Boulder area climb

put up in 1972 by Roger Briggs, then an aid-climbing practitioner.

Surprisingly, the first ascent was done free and protected by

pitons. Roger kept thinking to himself, "I'll go a little

further and then start aid climbing." Eventually he got so

close he wanted to finish it free and just barely did so. From

then on Roger Briggs was a free climber and one of the most

successful in the region.

Bruce had assured me that D&T

was similar in difficulty to Country Club Crack (5.11b/c) -

another climb that I was working on and very close to redpointing.

He rationalized away my previous performance with comments on the

heat and humidity. Eventually this prodding wore me down and I

thought I'd have a look. I figured my first attempt might be

ugly, but so was my first attempt on CCC.

Since the previous day was grueling for

the Loobster, we didn't start up the trail until noon. We

followed the Royal Arch Trail for about two miles to Sentinel

Pass. Here the trails drops down sharply to contour beneath the

Fourth Flatiron, before rising towards the Royal Arch. We headed

directly uphill, bushwhacking over boulder, logs, small cliffs in

an exhausting hike up another five or six hundred vertical feet

to Green Mountain Pinnacle.

On the north face

of this rock formation is the beautiful and intimidating crack

which is "Death and Transfiguration." Loobster took in

his breath and let out a respectful, "Wow!" Jim

Erickson described this route in his Rocky Heights guidebook as

"a becoming line, yet it is absurdly steep and strenuous."

Loobster already wasn't sure he could or even wanted to try

following the pitch. I said we'd worry about that when the time

came. We had the area to ourselves. Despite the classic nature of

this climb, the long approach and traditional nature of the climb

deters many of today's climbers. The only fixed gear on this

route are the two shiny bolts on top.

On the north face

of this rock formation is the beautiful and intimidating crack

which is "Death and Transfiguration." Loobster took in

his breath and let out a respectful, "Wow!" Jim

Erickson described this route in his Rocky Heights guidebook as

"a becoming line, yet it is absurdly steep and strenuous."

Loobster already wasn't sure he could or even wanted to try

following the pitch. I said we'd worry about that when the time

came. We had the area to ourselves. Despite the classic nature of

this climb, the long approach and traditional nature of the climb

deters many of today's climbers. The only fixed gear on this

route are the two shiny bolts on top.

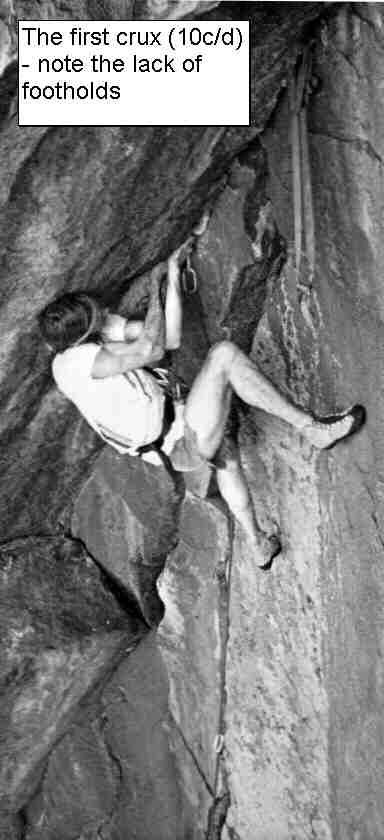

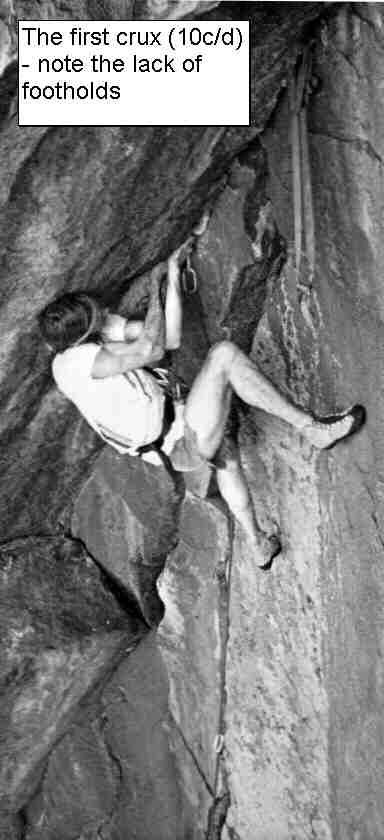

We geared up on the sloping slab at the

base and I moved off, climbing the flake directly above the slab

and the moving left and up to the base of the crack before

placing a piece. My rack consisted of stoppers through #3.5

Camalots with doubles for most units. The initial crack is steep

and fingers to tight hands in width. I placed red and yellow

Aliens on this section. The climbing initially is probably about

5.9 but there aren't very good rests. Above is a large, sloping

ledge but it is far enough to the left where I could only place

my left foot on it. Above here is the first crux: a strenuous,

undercling section that leads up and slightly right. The goal is

a large foothold well out to the right. I placed an orange Alien

right in the middle of this crux section - not sure that I could

complete the difficult climbing before coming off. This section

is rated 5.10c/d. I cranked hard and stretched right for the

foothold. And nailed it!

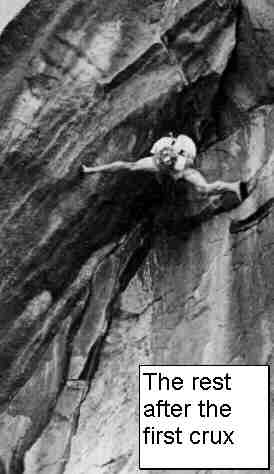

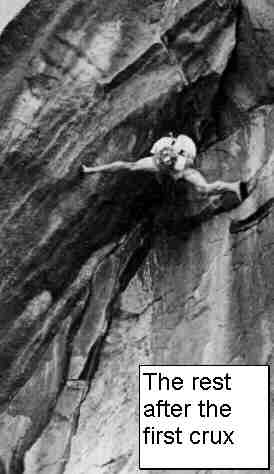

Here I got a reasonable rest. I could

drop one hand and shake out. The best position was to press my

right hand up against the underside of the roof above me. I could

use this force to keep me on the foothold, but it seemed possible

possible for my right hand to slip off.

The next section is rated only 10a, but

this has to be wrong. This is the most overhanging section and

goes immediately into the crux 5.11 moves so it isn't really

separate from the crux in my mind at all. Long legs and good

flexibility would be of use here to take advantage of some huge

stems. I didn't quite measure up to these reaches and my arms

suffered.

I think this climb is considerably more

difficult than the second pitch of Country Club Crack. Both

pitches have two 5.10 sections and one 5.11b section, but on CCC

I can get a no-hands rest before the crux and a nearly no-hands

rest between the 5.10 sections. Also, I can get another no-hands

rest before the first 5.10 section. On D&T there is but one

single-hand rest before all the hard climbing is over. This route

takes an enormous amount of endurance - my weakness and exactly

why I was here.

I launched into the overhanging roof on

initially good jams. I placed a #2 Camalot under the roof and

jammed up the right side. The jams got to be very tight hands

here and with no feet, I didn't think I could hang off one hand.

I stemmed my feet up as high as possible and then did a twist-lock

on my right hand jam while making a monstrous reach for the jug

at the top of the flake over the roof. I clasped the hold but

wasn't sure I could match hands since it practically involves

hanging from a single hand.

I barely pulled off the hand match and

then tried to get my feet set. I could either have my left foot

on a small hold or my right. I didn't have the flexibility to get

both feet on holds. I then pulled off the wrong piece from the

rack. It wouldn't fit in the tight hands crack. The next piece

barely fit - remember this piece as it will play a key role later.

I struggled to find a rest but failed. I hung on the rope and the

poorly placed camming unit.

The climbing above was overhanging

tended toward the right. Then the crack bent back toward the left

when it cleared another, smaller roof. I thought I remembered

that the crux was above this second roof. I was wrong. The crux

for D&T is just enduring from the foothold rest to the butt-cheek

rest just above the second roof, though the most difficult

climbing comes directly over the first roof - the climbing I

faced now.

Just like CCC, the crack widened to an

unusable dimension just over the roof and, also just like CCC,

passing this section involved a big reach to a marginal jam. I

stretched for the flared, tight-hands jam, matched the jam, and

stepped my feet up on top of the jug. This would be a rest if the

rock wasn't so overhanging. It was not a rest. I popped in a

piece and had to hang again. The next section involved a brutal

lieback/undercling to a lieback jam to a good hand jam where I

stuffed in a #3 Camalot and hung again.

I was right below the second roof now. I

climbed up once and latched the huge jug out on the arete. With

my left hand on the jug, I searched in vain for a hold in the

crack before falling off. This was a frustrating situation

because the hold for my left hand was so good. I felt I should

almost be able to just mantle up on the jug and stand up.

Unfortunately the leaning wall on the right, I was in a bit of a

flare, made this infeasible.

I think I fell off one more time before

figuring out this move. The key was working the feet up on the

right wall. There is a tiny hold in the crack itself and using

this with the mantle hold, I was able to work my feet up high

enough on the right wall to slip my left butt-cheek onto the jug.

Once this was done I could drop both hands! My first no-hands

rest since leaving the ground. I patiently worked in a good

Stopper and then struggled to stand up on the jug, but once I got

into this rest the main difficulties were over. I placed another

Stopper before I gained easy ground and then fought the terrible

rope drag - I didn't use enough slings - to the summit and the

two bolt anchor.

I was quite pleased with this effort

despite the three hangs and a couple of falls. I had done all the

moves free. This was a big improvement over my first and even

second effort on CCC. This will be a tough route for me to get

clean but now it is just a matter of linking it. Already I know

of a couple of ways to save energy: don't place a piece in the

middle of the lower crux and choose a smaller camming unit for

just over the lower roof. Once the gear is wired that should save

me at least one hang. The confidence of knowing about the no-hands

rest might save another. Then I'll just need to work on building

up my endurance.

The Loobster reluctantly tied into the

rope and started to follow. He climbed steadily up to the first

crux and took his first rest on the rope. From this point on it

would be critical where he decided to rest on the rope. He must

rest right next to a piece of protection. If not, he will swing

out away from the wall and might not be able to reach anything to

pull himself back on to the climb. Loobster completed the first

crux and got on the foothold rest. Then he climbed to the next

piece and rested again. He was just barely able to get back on

the climb this time and he climbed to the last piece below the

roof and pulled it. Unfortunately he then came off the climb and

swung out into space. The next piece was over the roof - the one

I placed while holding the jug at the top of the roof. The

Loobster had no hope of regaining the climb. He could just barely

touch the wall with his outstretched toe. That wouldn't be enough.

I lowered him to the ground.

I told the Loobster that I'd anchor the

rope at the top and rappel on a single line to clean the gear.

Then we'd do the 4th class route called the "Green

Sneak" to regain the summit to retrieve our rope. I started

down from the summit and placed a couple of directional pieces

before dropping off the edge to clean the gear. I popped out the

first two Stoppers easily, but then I was on overhanging ground.

I asked the Loobster to put the end of the rappel line on belay

so that he could stop me from swinging out too far and that he

could belay me on the rappel. With the Loobster locking off the

bottom of the rappel line, I could use both hands to pull myself

into the rock, lock-off with one hand in order to take the

tension off the rope, and then pull the piece. Once the piece was

removed, I'd swing out into space but I wouldn't go too far

before the Loobster stopped me by locking off the rappel line.

The Loobster and I had used a similar strategy when we

retreated off the first pitch of the Leaning Tower in Yosemite Valley, but,

as it turns out, there were crucial differences.

On the Leaning Tower not only wasn't the ground an issue, but when all the gear

was out of the pitch, the rope formed a sharp angle because the belayer was

not in-line with the top anchor. Neither of those situations existed here and

I would pay a big price for ignoring these obvious facts.

Just after I cleaned the second to last

piece and swung out from the wall, the last piece, the cam that

was a bit too large for the crack, popped! Immediately six feet

of slack rope fell to the ground - the rope that was going into

the cliff face and back out again. With a slack rope below me, I

no longer had a belay. My hands were not on the braking side of

my rappel device since I just had one hand in the crack and the

other pulling the piece. I fell like stone. Panicked with the

thought of certain death I frantically grabbed the rope in front

of me, but I was already moving too fast. The rope burned through

my hands and forearms giving me extremely painful cuts before I

instinctively released my grip. I wonder if I had just been tough

enough and endured the tremendous pain could I have stopped

myself or slowed down enough to avoid serious injury. Alas, I let

go. It all happened so fast. I knew I was in deep trouble. I

grabbed the rope. It burned me badly and I let go. I didn't

consciously think that letting go would surely kill me, but it

should have. I wish I could have endured the pain.

The Loobster had one chance to save me

and only a split second to react. If he could have jumped off the

sloping platform and down the slope fast enough to take up the

slack, my fall would have been halted. But with less than a

second to react, he had no chance. I landed flat on my back a few

feet from where he stood.

And now I'm crumpled at the base of the

climb waiting for help. My lower right leg stings sharply with

pain at the slightest movement and I fear I've broken it. The

intense pain in my hands has subsided somewhat by keeping them

clenched tightly. I know the big problem is my back. A fall of

that distance should do tremendous damage. I am terrified to move

anything for fear of permanent spinal damage. It is absolutely

amazing that I suffered no head injury. I was not wearing a

helmet and fell over forty feet (8 weeks later I returned to

Green Mountain Pinnacle and measured this distance: 75 feet!)

onto my back amongst a sea of rocks. The Loobster would revisit

this site a few days later with another friend and both could not

believe that survival was an option. Though at the time I didn't

feel lucky.

I went with various stages while lying

there. I composed myself and promised myself to get all the

rescuers names and addresses. I was so thankful that I'd see my

wife and kids again. I cried with self-pity at my situation and

injuries. And then I composed myself again. I called for help a

number of times, but I was too remote. I promised myself to be

matter-of-fact when the rescuers got to me, but then I broke down

with emotion.

The Loobster headed downhill at a

reckless pace. He hit the Royal Arch trail considerably downhill

from Sentinel Pass, where we left the trail on the way up, and

ran for help. Each person he passed, he'd query them: "Do

you have a cell phone?" After a number of disappointments,

he struck pay dirt.

"Dail 911," he commanded. The

Loobster didn't want to learn how to work this guy's cellular

phone. He wanted help on the line. The dispatcher got things

moving and instructed the Loobster to continue down the trail

until he ran into help.

Further down the Loobster recognized a

group of three climbers who had been climbing on the Spaceship, a

crag just above where we were. Once he confirmed they were this

group, he told them, "My friend is badly injured up there

and I'm not from around here. I don't think I can lead the rescue

group back to him. I need you to do that. Will you do it?"

He responded affirmatively. Yet another person to unselfishly

help me. The list would grow awfully long.

Further down the trail the Loobster met a ranger coming

up the Bluebell Shelter road and flagged him down. He knew about the situation

and told the Loobster to get in. Further up they met the guide and Loobster

got out to make room. Loobster was told to wait for the Rocky Mountain Rescue group. RMR

had just finished a practice session in Boulder Canyon so they were all assembled

and ready for action. Sixteen members showed up in just a few minutes. Glenn

Delman threw the 45-pound litter on his back and started running up the

trail! The adrenaline of helping someone in dire need fueled him.

As it turns out Glenn is a member of my

wife's running group and had been at our BBQ party the day before.

He worked the ropes on the entire rescue and would be familiar

with my first name and my wife's first name, but never make the

connection who I was until the next day when he received an Email

about my accident.

The first person to reach me was a

ranger along with the drafted guide who had been climbing on the

Spaceship. I'm lucid and answer all their questions. Soon more

people arrive, including the Loobster. The Loobster still has to

climb Green Mountain Pinnacle and get the rest of my gear down

and the rope. Then he'll have to pack up two packs worth of gear

and carry it all out.

Soon a paramedic arrives on the scene.

While everyone who helped me was very professional and very

compassionate, this paramedic inflicted a lot of pain on me.

Unintentional, of course, but nevertheless tremendous pain. This

came about due to his attempts to get an IV into my left arm.

After cleaning my arm with alcohol and thereby burning my over

wounds intensely, he warmed me, "This is going to hurt -

it's a very large needle. He was right. I yelled in pain.

Unfortunately, it didn't pierce the vein. A second attempt also

failed and he couldn't bring himself to torture me a third time.

After I was carefully placed in the

litter, wrapped in a device called a bean bag, they attached a

neck brace. This seemed to be an unnecessary precaution as I had

already been moving my head around quite a bit, though I've heard

of instances where someone was able to move after a serious back

injury and did permanent spinal damage to themselves by moving

around. They had to take every precaution. Nevertheless, this

brace would be the cause of much discomfort to me. It choked me

and eventually had to be loosened up a bit. It wouldn't be

completely removed until after x-rays were taken in the hospital.

Now another medic came at me intent on

getting an IV in my arm. I tried to talk them out of it, saying

that I was completely lucid and fine. They said they couldn't

take a chance that I'd go downhill on the evacuation. As it turns

out, they were right about that. A woman successfully got the IV

into my right arm, having given up on the left arm. Once this was

done, they were set to move me.

The evacuation was done by stringing

sets of ropes from tree anchors. The terrain was not technical

climbing, but it was quite steep and very rough with logs,

boulders, small cliffs, trees, bushes, etc. There was no way to

simply hike out carrying the litter. The litter itself was

lowered on ropes, but at the same time at least four rescuers

lifted and carried it over the terrain. This was extremely

physical work and the litter crew was rotated regularly. I tried

to remain courteous and responsive as there was nothing else I

could do.

After an hour and a half of leapfrogging

down ropes, I started to get tired. I guess I was going into

shock. My mind was working fine, but I felt so tired and so

sleepy. At first I could just barely talk because I was so tired,

but then I couldn't talk at all. It was the most bizarre

condition I've ever experienced and more than a little bit

frightening. Basically, I forgot how to talk. I knew what words I

wanted to say, but I just couldn't say them. I babbled around

trying to say the word "Sunday" when asked what day it

was. I finally got them to list the days of the week and nodded

when they got to Sunday. The next question was who was the

President and I could not figure out how to say the word "Clinton."

This had nothing to do with my political alignment, but a

baffling inability to form words. This condition went away once I

got a bit stronger further down, but it was still very hard for

me to talk. I was just so tired.

My condition worried the rescuers and

they seemed to double their efforts. I couldn't see much from my

cocoon, but eventually we left the ropes behind and were walking

down the trail and carrying the litter. This did not occur as

soon as the Royal Arch trail was reached because the trail itself

is quite steep and with tight switchbacks. Switchbacks and litter

carrying don't mix very well.

After more than two and a half hours in

the litter, I was slid into an ambulance which apparently was up

at the Bluebell Shelter. The Loobster was there and called to me,

but I couldn't see him and still was unable to respond. The doors

were closed and soon I was at the Boulder Community Hospital.

Looking up from the gurney in the

emergency room I was shocked to see the face of my friend, Dale

Wang. Dale is a good friend of my bother's and an avid climber.

It turns out that six weeks ago Dale had a similar climbing

accident and broke his L1 vertebra. I was once again subjected to

the IV torture - apparently the field IV is not considered

sterile enough despite the alcohol treatment. The emergency nurse

twice failed to get the IV in my left arm after stinging me with

alcohol. I yelled in pain. Never again will I let someone attempt

to get an IV in my left arm. It must be something about the veins

in that arm because both of these medical people cannot be this

incompetent. She succeeded adding a second IV to my right arm

after painfully stinging me with alcohol and jabbing the huge

needle into my arm.

My wife, Sheri, was already at the

hospital but wasn't very concerned as the Loobster down played

the entire incident so he didn't panic her. Loobster mentioned

that I didn't want a rescue and Sheri concentrated on that. She

finished feeding the kids, loaded them up, and headed to the

hospital. She brought Loobster and I some pizza to eat and

expected to be bringing us home. The Loobster got the hospital a

bit before I did and went right up to Sheri with tears in his

eyes and embraced her. Unlike me, the Loobster is not an

emotional person and now Sheri was concerned. I was then wheeled

in strapped into a full back and neck brace. Sheri tensed for the

worst. Later, while holding the phone so that I could talk to my

brother on the phone, Sheri fainted. I could see her getting

woozy and asked what was the matter. She sat down, but then stood

back up. I was afraid she fall and injury herself. I kept telling

her to sit down, but she ignored me. We were the only ones in the

room and I started called, "Help! Help!" so that

someone would come help Sheri before she hurt herself.

Sheri had called my Mom to notify her of

the situation. She immediately got in the car and drove the forty

minutes to my house so that she could watch the kids. The

Loobster took the kids back home. When my Mom got there the

Loobster returned to the hospital.

After countless x-rays, they removed my

neck brace and told me I had a broken back. A CAT scan was

necessary to determine the extent of the damage. Thirty minutes

later I was done getting scanned. The results were as positive as

possible - given that I had a broken

back. The L2 vertebra was broken, but

it did not threaten my spinal column. In the morning, the

orthopedic would determine if surgery were necessary. Finally I

was wheeled upstairs to a private room and hooked up to morphine

so that I could sleep. I shooed the Loobster and Sheri back home

to sleep and I spent a fitful night between morphine injections.

The orthopedic surgeon visited me the

next morning and notified me that surgery would not be required.

I was relieved, of course. I was told that a 100% recovery was

expected but that it would take a year before my back didn't hurt

me. In six weeks I'd be able to start exercising with some easy

bike riding. Considering the alternatives, this sounded pretty

good. Until then I wasn't supposed to bend, turn, twist, or lift.

I'd be quite a burden on my wife.

Which brings me to the luckiest part of

this whole mess: my family and friends. They are the greatest

anyone could hope to have. And therefore far more than I deserve.

But I'm so thankful. I was flooded with calls, visits, Emails,

letters, flowers, balloons, and dinners. My Mom moved into our

house for a full week. We couldn't have gotten by without her.

She is an angel of compassion. A more giving person I have never

known. This was just the latest example. My sister Kim brought

dinner on Wednesday night. My sister Brook and her family came on

Thursday night with steaks. Friday night my Mom made dinner.

Saturday night I was invited to the Trashman's house. I will

surely be monstrously fat by the time I'm healed, but I'll also

have an incredible layer of goodwill. I glow from the inside with

the appreciation and affection and love for my family and friends.

To quote Lou Gehrig, "I might have been given a bad break,

but I consider myself the luckiest man in the world."

Postscript:

Since my accident, I've found out that

three friends have suffered back injuries from climbing accidents:

Dale Wang, Ken Leiden, and Clint Cummins. Also, the noted aid

climber Warren Hollinger suffered a career ending back injury

when he took a fall climbing on the Rainbow Wall in Red Rock

Canyons near Las Vegas.

There is no doubt that this accident was

caused by my personal errors. In retrospect it seems amazing that

I could not recognize the danger I was before it was to late.

Most climbing accidents are caused by human error and this was no

different. But this certainly wasn't the first time I had made an

error. It was just the first time I had to pay a high price.

Numerous other climbing partners have said the same thing to me.

There aren't so arrogant as to think that they are alive or

healthy because they've never made an error and nor was I before

this. I knew accidents were caused by climbers making errors and

whenever I read about them my reaction wasn't: "Oh, they

screwed up. That will never happen to me because I never screw up."

My reaction was more like: "Damn, that sucks. I've done

similar things before, but this or that didn't happen to me at

the same time. I'll have to re-think that practice." I've

learned a lot from reading about the climbing accidents of others

and it is my intent here to help others avoid a similar accident

to mine.

These mistakes typically happen on

"easy" ground where things are too "easy" to

require full concentration. I don't get hurt leading 5.11 since I

expect to fall off at any time and place lots of good gear. I

have much more potential for serious injury on 5.7's where I

might run things out considerably. If there was a runout of 12

feet on a hard climb, I might do it, but I would be concentrating

very hard and very aware of what would happen if I fell. But on 5.6

ground I am likely to be much more careless. Or rappelling…

What I should have done instead:

All climbers are taught that when

rappelling to never let go of the braking side of the rope. I've

taught this myself to a number of climbers and I'd always stress

"whatever else you do, don't let go of the rope with your

brake hand." Having said all that, there are times when you

need to free both hands, but whenever a climber is doing such a

radical maneuver that goes against all the basic instruction, he

should be triply sure he knows what he's doing and that he is

safe. I didn't do this.

I should have taken responsibility for

myself and always kept the rope wrapped around my leg when

freeing both hands. This is my usual practice. I didn't do it

here because I thought the Loobster could belay me and I didn't

want him squeezing my leg as he helped pull me into the rock.

This would have been a minor discomfort and obviously I should

have kept the rope around my leg.

Another option was to use a prusik. I've

never done this in the past and disdained this strategy as overly

protective, more complicated, and slow. While I still believe

that in routine rappelling situations, it might be appropriate in

more unusual and dangerous situations. This clearly was a more

dangerous rappel situation and I should have taken extra

precautions and not less. But the use of a prusik is not a

panacea and there is definitely debate in the climbing world on

whether this makes the rappel safer or not. See this article for

a more complete discussion:

http://www.dtek.chalmers.se/Climbing/Hardware/prusik-on-rappel.html

If there was any doubt as to my ability

to clean the route, I should have downclimbed the 4th

class route back to the base and had the Loobster ascend the same

route so that he could belay me from above (this route is about

120 feet long.) Then I could have climbed the route again, on a

toprope while cleaning the gear.

The things that went right and

allowed me to survive:

Falling over forty feet without a helmet

onto your back in a very rocky area should kill you. If you're

lucky it should paralyze you or permanently disable you in some

way. My prognosis is 100% recovery. I have no marks on me from

this incident (besides fading rope burn scars). I worked two days

after the accident and spent only 24 hours in the hospital. Here

are the things that went right for me:

![]() I

was lucky, lucky, lucky!

I

was lucky, lucky, lucky! ![]() I landed in only

possible spot where I could have survived.

I landed in only

possible spot where I could have survived.

![]() I

was very fit at the time and maybe this helped me survive

the impact.

I

was very fit at the time and maybe this helped me survive

the impact.

![]() The

Loobster moved extremely quickly in getting me help.

The

Loobster moved extremely quickly in getting me help.

![]() RMR

was fully assembled having just completed a practice and

appeared on the scene very quickly..

RMR

was fully assembled having just completed a practice and

appeared on the scene very quickly..

The things that had to go wrong for

this to happen:

![]() If

I was in worse climbing shape or my head wasn't into

leading. On the approach I thought there was a definite

possibility that I would only get a ways up it before

resorting to toproping.

If

I was in worse climbing shape or my head wasn't into

leading. On the approach I thought there was a definite

possibility that I would only get a ways up it before

resorting to toproping. ![]() If the Loobster

was in better climbing shape - he had not been doing much

hard climbing this year - and he was able to follow the

pitch.

If the Loobster

was in better climbing shape - he had not been doing much

hard climbing this year - and he was able to follow the

pitch.

![]() If

the Loobster decided not to follow the pitch at all. Then

the gear would have extended almost to the ground and the

piece popping over the roof wouldn't have been a problem.

If

the Loobster decided not to follow the pitch at all. Then

the gear would have extended almost to the ground and the

piece popping over the roof wouldn't have been a problem.

![]() In

fact, if the Loobster had either climbed one piece higher

or lower, than the bottom piece wouldn't have been the

only questionable piece - the only piece with much of a

chance to pop.

In

fact, if the Loobster had either climbed one piece higher

or lower, than the bottom piece wouldn't have been the

only questionable piece - the only piece with much of a

chance to pop.

![]() The

piece had to pop. If it didn't then the danger would have

been clear before it was too late.

The

piece had to pop. If it didn't then the danger would have

been clear before it was too late.

![]() If

the Trashman had joined us that day, as was originally

planned, he'd have surely been able to climb the route.

Then I wouldn't have had to clean it on rappel.

If

the Trashman had joined us that day, as was originally

planned, he'd have surely been able to climb the route.

Then I wouldn't have had to clean it on rappel.

Though I've had a bad accident, things

went extremely fortunate for me. I've been spared. Probably not

to do more climbing and running, but to raise two great boys. Of

course, I'll try to do all three…

Other Near Death Experiences

This accident prompted me to think of other incidents where

luck helped me survive a near death experience, or stupidity

brought me very close:

![]() I taught myself how to

rappel out my dorm window from a book. The first time I

leaned back to try it out my biner configuration wasn't

right. I grabbed the window frame and pulled myself back

in for another look at the book.

I taught myself how to

rappel out my dorm window from a book. The first time I

leaned back to try it out my biner configuration wasn't

right. I grabbed the window frame and pulled myself back

in for another look at the book.![]() On one of my first outings on real rock

my partner got shutdown trying to lead The Owl on Dome

rock. I didn't even get to leave the ground. Hence I

volunteered to rappel off the top of the Dome rock to

retrieve the gear that my partner had left to retreat. It

was dark at the time and I rappelled right into a knot

and got stuck. I clipped my myself into a nearby piton

via the gear sling I had over my head! Then I took myself

off rappel and fixed the problem. Stupid!

On one of my first outings on real rock

my partner got shutdown trying to lead The Owl on Dome

rock. I didn't even get to leave the ground. Hence I

volunteered to rappel off the top of the Dome rock to

retrieve the gear that my partner had left to retreat. It

was dark at the time and I rappelled right into a knot

and got stuck. I clipped my myself into a nearby piton

via the gear sling I had over my head! Then I took myself

off rappel and fixed the problem. Stupid!

![]() As I became a solid

5.7 leader I wanted to lead the notorious Bulge since it

was 5.7 R and that would confirm my 5.7 leader status. I

got through the first two pitches, but struggled at the

crux bulge on the third pitch. Eventually, I got so tired

that I just fell over backwards for a 45 foot fall! I

fell onto an ancient quarter inch bolt. I fell from the

crux to below the belay at the start of the pitch.

Thankfully the wall is steep and I didn't hit anything

until I swung into the wall, but this was very lucky -

the wall isn't that steep. I wore no helmet and fell head

down. Most of the force when I hit the wall was taken by

my elbow and then my head hit - both were bleeding. All

my fingertips were bleeding from sliding off the holds.

My glasses fell the full 250 feet to the ground and broke.

My partner, Eric Schneider, lowered me down to the first

belay and we retreated. I had to drive my motorcycle back

to our apartment without my glasses because Eric didn't

know how to ride a motorcycle..

As I became a solid

5.7 leader I wanted to lead the notorious Bulge since it

was 5.7 R and that would confirm my 5.7 leader status. I

got through the first two pitches, but struggled at the

crux bulge on the third pitch. Eventually, I got so tired

that I just fell over backwards for a 45 foot fall! I

fell onto an ancient quarter inch bolt. I fell from the

crux to below the belay at the start of the pitch.

Thankfully the wall is steep and I didn't hit anything

until I swung into the wall, but this was very lucky -

the wall isn't that steep. I wore no helmet and fell head

down. Most of the force when I hit the wall was taken by

my elbow and then my head hit - both were bleeding. All

my fingertips were bleeding from sliding off the holds.

My glasses fell the full 250 feet to the ground and broke.

My partner, Eric Schneider, lowered me down to the first

belay and we retreated. I had to drive my motorcycle back

to our apartment without my glasses because Eric didn't

know how to ride a motorcycle..

![]() While climbing the

DNB in Yosemite, a basketball sized rock came screaming

toward us. It blasted into the wall only a few feet above

it and disintegrated.

While climbing the

DNB in Yosemite, a basketball sized rock came screaming

toward us. It blasted into the wall only a few feet above

it and disintegrated.

![]() In September 1989,

frustrated that I didn't have any climbing partners, I

walked into the Dana Couloir (on Mt. Dana) to solo it.

This couloir is only about 50 degrees or so, but I got

there very late in the morning. I didn't start up it

until 11 a.m. Halfway up the couloir I heard a tremendous

roar and looked up to see a boulder the size of a VW Bug

and all its satellite rocks coming straight for me. On

brittle dinner plating ice I instinctly slammed my tools

in with one stroke as I sprinted right to avoid certain

death. The rocks missed me but I was severely shaken. I

didn't want to downclimb the hundreds of feet I had

already come up, but I feared going up also. I

practically sprinted up the remainder of the couloir so

that no other rocks would fall on me. It took me fully

fifteen minutes before I could breathe normally after

collapsing at the top.

In September 1989,

frustrated that I didn't have any climbing partners, I

walked into the Dana Couloir (on Mt. Dana) to solo it.

This couloir is only about 50 degrees or so, but I got

there very late in the morning. I didn't start up it

until 11 a.m. Halfway up the couloir I heard a tremendous

roar and looked up to see a boulder the size of a VW Bug

and all its satellite rocks coming straight for me. On

brittle dinner plating ice I instinctly slammed my tools

in with one stroke as I sprinted right to avoid certain

death. The rocks missed me but I was severely shaken. I

didn't want to downclimb the hundreds of feet I had

already come up, but I feared going up also. I

practically sprinted up the remainder of the couloir so

that no other rocks would fall on me. It took me fully

fifteen minutes before I could breathe normally after

collapsing at the top.

![]() I once pulled a

"Lynn Hill" and followed a route called "Wet

Kiss" (5.9) in Pinnacles National Monument in

California without my harness tied on. I had been

interrupted while putting it on (something I will not

allow anymore) and didn't finish the job. Thankfully I

noticed the error before rappelling off the top.

I once pulled a

"Lynn Hill" and followed a route called "Wet

Kiss" (5.9) in Pinnacles National Monument in

California without my harness tied on. I had been

interrupted while putting it on (something I will not

allow anymore) and didn't finish the job. Thankfully I

noticed the error before rappelling off the top.

![]() While descending the

gully just west of the Awahnee Buttress and just as I was

at the very edge of a 100 foot drop, the Loobster

dislodges 4' by 4' by 2' boulder just above me.

Instinctively, I dump up and let the boulder pass beneath

me. Upon landing I slap my hand down on the rock in from

of me so hard that it hurts for the rest of the day.

Immediately the Loobster's hand shot out and grabbed my

wrist. The boulder tumbles over the edge starts a

cacophony of tumbling rocks down the gully. We knew no

one else was up here and were glad for that because

anyone in the gully below would have stood a good chance

of being crushed.

While descending the

gully just west of the Awahnee Buttress and just as I was

at the very edge of a 100 foot drop, the Loobster

dislodges 4' by 4' by 2' boulder just above me.

Instinctively, I dump up and let the boulder pass beneath

me. Upon landing I slap my hand down on the rock in from

of me so hard that it hurts for the rest of the day.

Immediately the Loobster's hand shot out and grabbed my

wrist. The boulder tumbles over the edge starts a

cacophony of tumbling rocks down the gully. We knew no

one else was up here and were glad for that because

anyone in the gully below would have stood a good chance

of being crushed.

A parody of

this climbing accident - Notice: Strictly humor!

Or so I thought. I came to about 30 seconds later

as if awakening from a dream. My breathing wasn't uncontrolled

gasps, but measured draws. The Loobster was hovering over me in

an agitated state. I was in pain and knew I had just fallen a

considerable distance onto my back. "How bad am I?" I

asked the Loobster, expecting his response to be "Not too

good, Bill. You've lost a leg, your head is cracked open, and

your bleeding profusely from your back." I forgot his

response, but I soon knew I wasn't bleeding. Initially my most

intense pain was in hands and arms. They had stinging rope burns

on them. I was slumped on my side and so afraid to move. I knew I

had a back injury and cautiously tried to move and feel my feet.

They worked.

Or so I thought. I came to about 30 seconds later

as if awakening from a dream. My breathing wasn't uncontrolled

gasps, but measured draws. The Loobster was hovering over me in

an agitated state. I was in pain and knew I had just fallen a

considerable distance onto my back. "How bad am I?" I

asked the Loobster, expecting his response to be "Not too

good, Bill. You've lost a leg, your head is cracked open, and

your bleeding profusely from your back." I forgot his

response, but I soon knew I wasn't bleeding. Initially my most

intense pain was in hands and arms. They had stinging rope burns

on them. I was slumped on my side and so afraid to move. I knew I

had a back injury and cautiously tried to move and feel my feet.

They worked. On the north face

of this rock formation is the beautiful and intimidating crack

which is "Death and Transfiguration." Loobster took in

his breath and let out a respectful, "Wow!" Jim

Erickson described this route in his Rocky Heights guidebook as

"a becoming line, yet it is absurdly steep and strenuous."

Loobster already wasn't sure he could or even wanted to try

following the pitch. I said we'd worry about that when the time

came. We had the area to ourselves. Despite the classic nature of

this climb, the long approach and traditional nature of the climb

deters many of today's climbers. The only fixed gear on this

route are the two shiny bolts on top.

On the north face

of this rock formation is the beautiful and intimidating crack

which is "Death and Transfiguration." Loobster took in

his breath and let out a respectful, "Wow!" Jim

Erickson described this route in his Rocky Heights guidebook as

"a becoming line, yet it is absurdly steep and strenuous."

Loobster already wasn't sure he could or even wanted to try

following the pitch. I said we'd worry about that when the time

came. We had the area to ourselves. Despite the classic nature of

this climb, the long approach and traditional nature of the climb

deters many of today's climbers. The only fixed gear on this

route are the two shiny bolts on top.