The Elk Mountain Grand Traverse Backcountry Ski Race

Winter

Training for Grand Traverse Ski Race

Winter

Training for Grand Traverse Ski Race

Interactive

Map - Photos

- Results

March 28, 2009

Holy cow! This race is tough. It was eye-opening. I liken it

to ultra-marathons, where you see people who you wouldnÕt think could hold a

candle to you in mountain adventures, passing you. This is an event you have to

learn, because pure fitness isnÕt nearly enough to conquer this race. The Grand

Traverse is very serious, very committing and so very different from nearly any

other competition IÕve done.

Homie was the primary motivator to enter this race, though I

had planned to do it the year before with Kirsten. That plan fell through, and

this one almost did at the very last minute due to a behemoth storm I was

greatly unaware of until the day before the race itself. This race, though, is

part of my plan to do each of ColoradoÕs signature outdoor endurance events.

IÕve done adventure races, the Pikes Peak Marathon, and last year I did

Leadville. And, of course, the Rattlesnake Ramble. The logistics of this race

are daunting, at least for your support personnel due to the fact that it is a

6-hour or more drive from Boulder to Crested Butte. Then of course thereÕs the

6-hour drive from Crested Butte to Aspen (you can practically ski there

fasterÉwell, if you are Mike Kloser thatÕs almost true). Plus the final and

relatively short 4-hour drive from Aspen back to Boulder. The race offers you

no return transportation to Crested Butte requiring you to have driver support.

Because of this burden on others, this was a one-and-done event for me.

As it turns out, I vastly under-estimated this race. My

friend Kirsten wondered before the race, ŌIÕll be interested to hear if you

think this race is harder than the Leadville 100.Ķ That statement seemed

ridiculous to me at the time. This race was only 40 miles with only 7000

vertical feet of climbing. But if you compare those numbers with running along

the trails of the Leadville 100, you are in for a big, big surprise. Kirsten

was a professional runner, so obviously very fit and fast, but I didnÕt think

she was an ultra-athlete, despite her doing this race five times. My respect

for her, having already been substantial, is now simply immense.

I decided to run my first marathon so that I could say, ŌA

marathon is no big deal.Ķ I wouldnÕt dare saying that without running one

beforehand. I envisioned the Grand Traverse the same way. But with the marathon

I did a number of races building up to that distance and even got completely

crushed in a 30k where I could barely walk afterwards. Hence, by the time I

toed the line for my marathon I knew I was in for a Ōbig deal.Ķ While I did

some training of up to nearly 20 miles on skis and over 5000 vertical feet, it

was nearly all below tree line and it was all safe and easy. Plus, anyone who

thinks 40 miles on skis is twice as hard as 20 miles doesnÕt know the

mathematics of endurance events. ItÕs four times as hard because:

Perceived

difficulty = (total distance)2

Any intrepid adventurer must have a bad memory so that they

forget the suffering involved and I suspect that will eventually happen to my

view of this race, but as I write this on the day after the event, I could not

imagine doing it again. It is an ultra in every sense of the word and much more

committing than any running event IÕve done. While it is very hard to compare

it to ultra-running since it is so different, this event is considerably harder

than the Lake City 50 and, while much shorter, in some ways compares to

Leadville. It takes much more overall mountaineering knowledge and experience

and much more skill than ultra-running and I suspect that many that who do Leadville

couldnÕt do this event and visa-versa. ItÕs sort of like swimming the English

Channel. Though the Channel has been swum in less than seven hours, if an

endurance athlete that wasnÕt an open water swimmer tried it, theyÕd nearly

zero chance of making it. If you arenÕt an experienced backcountry skier, it

doesnÕt matter what youÕve done endurance wise, you arenÕt finishing the Grand

Traverse. Finally, you canÕt just drop out of this race whenever you want, like

in must ultras.

The race flyer says, Ōbecause of the extraordinary nature of

this event only teams of two will be able to compete.Ķ I thought this was

mainly BS, sort of like the Pikes Peak Marathon calling itself ŌAmericaÕs

Ultimate ChallengeĶ, there is a lot of truth here. Rescue from this race is so

difficult that they clearly state at the pre-race meeting that you will not be

snowmobiled out if you gear is broken. You will not be saved if you are too

cold. With 300 people deep in the backcountry, they couldnÕt rescue very many.

If a major event blew in when many races were over Star Pass, or over Taylor

Pass, it could seriously be a disaster. This has to be a very stressful event

to put on. In order to ease that stress and give racers a chance of surviving

such an event, each team is forced to carry a lot of mandatory gear, including

a sleeping bag, bivy bag, stove, first aid kit, spare binding, repair kit,

spare baskets, etc. I found myself fantasying about doing the race solo,

staring at 6 a.m. without any of the required gear and doing the race entirely

in the daylight with a very light pack. I might be able to pull that off, under ideal snow and weather conditions, but

if I didnÕtÉI could actually die. Seriously, if a storm came in and you had no

form of shelter with you, with no way to make it to any shelterÉ

Despite all the signs that this is not your average event, I

was very relaxed and confident at the start. Part of this was due to no

performance pressure. I did know that to go fast, IÕd have to at least do the

race once and learn its secrets, so I wasnÕt worried about my placement or

time. I still had goals however. They were, in order:

1.

Be a good partner to my great friend Homie

2.

Have fun and enjoy the experience

3.

Finish the race

4.

Break 12 hours

The last one was a ridiculous goal considering how

completely ignorant I knew I was. It was based on KirstenÕs best time of just

over 13 hours and her pumping me up that IÕd be a stronger racer than she was.

IÕll also admit that it came about because of Kirsten building up the race to

be some epic event and my desire to prove it was Ōno big deal.Ķ She was

absolutely right and I was absolutely wrong. But my ego wouldnÕt allow me to

comprehend what was coming.

We almost didnÕt even start this race. My family and I were

returning from an RV trip to the Grand Canyon when the biggest storm of the

year hit the front range. We couldnÕt make it back to Superior, where all my

race gear was located. The Boulder area was pretty much paralyzed with offices

closing at mid-day. Homie and I talked numerous times on the phone and I

decided to stop driving at Edwards, which is just west of Vail. I told Homie it

didnÕt look like the race was going to happen for us. I offered to pay our

entire entry fee since I was the one who couldnÕt get back home. He was having

none of it. We were going to make the start of the race if Homie had to move

the mountains themselves.

He drove to my house and gathered all my gear. His wife Lori

shuttled their two little girls to her parentsÕ house. Then they drove all the

way to Edwards to pick me up. Tired, we decided to spend the night there and

drive to Crested Butte in the morning. Homie did all the driving the next day.

WeÕd made it, all because he wouldnÕt be denied.

The pre-race meeting was held at a hotel at the base of the

ski area. We spent a good portion of the day here, getting our gear organized,

check in for the race, eating the catered lunch, and going through the

mandatory gear check. The pre-race meeting was inspiring and sobering. The race

directors are two women and one got really choked up talking about how this was

the biggest field ever and that it filled in one day. We were told the course

was in great condition, despite getting 30 inches of snow over the past four

days. Homie and I figured that would help us versus the icy/crusty conditions

that are common in the spring. Then we were told,

ŌWe will not rescue because you are cold. We will not rescue

because you are tired. We will not rescue you if your gear breaks. Take care of

yourselves and your partner. DonÕt become separated. If you get too far away

from your partner, youÕll be DQed. DonÕt get too wet with sweat. But on your

shell before you hit the wind. ItÕs going to be in the single digits at the

start. Where your neck gaiter and keep your skin covered.Ķ

We all filed out onto a wide, flat, Nordic trail for the

start. Racers were at least 10 across and Homie and I worked out way up to

about the middle of the field. We were told earlier that day that for the first

time there would be a rolling start behind a snowmobile. This was so that

things remained under control through some barbwire fences. The race director

told us that the snowmobile would be going really slow so that everyone could

jockey for a position before the start. From where I stood the snowmobile appeared

to be going about 15 mph. That isnÕt slow and the field quickly spread out into

a long line. I found out later that they decided against slow start at the last

minute. Within a mile the leaders seemed to be half a mile ahead.

The race started right on time, at midnight. What a bizarre

sight: 300 backcountry skiers, all donned in headlamps, blasting down the

course, poles flying, legs kicking. I was wearing one of PetzlÕs new MYO RXP headlamps

that has regulation. It kept up a constant, very bright light for six hours

before I had to turn it down. This was key in skiing fast down the backside of

Crested Butte and it kept me out of the ŌtunnelĶ that weaker headlamps put you

in.

Our plan for the race was for me to stay behind Homie for

most of the time during the night. IÕm a faster downhill skier so we thought if

I stayed behind Homie on the descent of Crested Butte, weÕd be able to stay

together in the dark. So, as soon as the gun went off, I cruised into the lead.

I know that wasnÕt the plan, butÉwell, you knowÉ I think I might have been

excited.

But I reined it in quickly and we generally skied right next

to each other as we skied around a horseshoe-shaped course in the Nordic park. Someone

stabbed HomieÕs pole or tripped him because he went down. It would be the first

in a long series of falls for Homie. On the drive home later that day, Homie

would guess he hit the ground thirty to fifty times.

The group was spreading out, but we were still following ski

tails. We crossed through the break in the barbwire fence and some skiers

stopped to put on skins. Homie had fish scales and I had extra blue wax and

both were gripping well, so we continued without skins. Soon we were on a

singletrack through the woods and I made sure Homie was in the lead.

Occasionally a team would have trouble with a tricky section and weÕd be

clogged up behind them. I felt like I was hardly working and wanted Homie to

pass, but didnÕt say anything. I knew it wasnÕt going to matter much at this

point in the race.

In a little under an hour we covered the 3.5 miles and

400-500 vertical feet to the base of the Crested Butte ski area. There was a

small crowd here cheering us on. I stopped here to put on my kicker skins while

Homie kept going. I was really quick putting on the skins and soon caught up to

Homie. I felt we were going great and were just going along at a pretty

comfortable pace, but I could already tell that Homie was working harder than I

was.

Homie had put in a Herculean effort to get us to the

starting line, including sacrificing a lot of sleep. He was also a bit sick and

this big effort in frigid weather wasnÕt making him stronger. But Homie never

complains and Homie doesnÕt DNF. Or DNS. IÕve done both and I knew entering

with him would immediately increase my chances of finishing.

Both of our Camelback hoses were frozen solid and we both

stopped to try and clear the hoses. For me this meant putting the entire

bladder down inside my bibs. If IÕm wearing a shell this works fine, as a lot

of heat is trapped inside, but I wasnÕt wearing a shell. If the tube was

exposed at all to the air, it wouldnÕt defrost. I had to make sure it was well

stuffed down into my pants. After 15 minutes or so, I was able to drink again,

but whenever I switched the Camelback to my pack, the hose froze. This happened

to everyone, including the people with fully insulted hoses. It was just too

cold out.

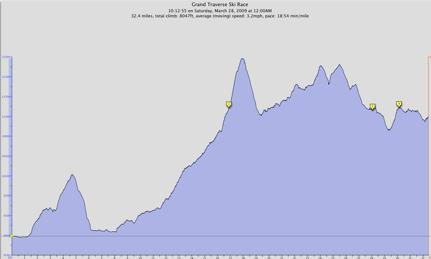

Figure 1: This is most of the race

profile - my watch stopped two hours before the finish. The first bump is

Crested Butte. First, there is the climb to the base of Crested Butte and then

the climb up the ski area. The huge climb is the one up to Star Pass. The Ō1Ķ

marks the Friends Hut. The next major peak is actually higher than Taylor Pass.

The Ō2Ķ marks the Barnard Hut. The Ō3Ķ just marks the top of the worst climb on

Richmond Hill.

I stripped off my skins at the top of the Crested Butte

climb and Homie got out ahead of me. I quickly caught him on the smooth descent

of the backside ski run. I was enjoying zipping down in the dark when I

remembered that Kirsten said it would be hard to regroup at the bottom. I

stopped put my headlamp in flashing mode and looked up the mountain, calling

out, ŌHomie,Ķ to each headlamp coming by. When I regrouped with Homie I told

him IÕd now stay behind him, but he wanted me in front. I used the flashing

headlamp trick to find him a couple more times.

The final steep descent exited the ski area and the snow

changed from a wide, packed trail to just a single set of tracks and powder. I

watched a number of skiers fall in big heaps here, but Homie made it down

standing. I think Homie then took over the lead and we kicked and glided for

the next two miles down the valley. Here it is was really cold, especially

after skiing down the descent without a shell. I had to ball up my hands, even

though I had a chemical heater inside my light, pile gloves. I had a big pair

of Dachstein wool mitts in my pack, but I didnÕt want to use them until

necessary.

After about two hours and eight miles we started up the

10-mile, 3500-foot climb to Star Pass. Most of this climbing was gentle and I

went a mile or so with my kick wax before switching to kicker skins. Our hose

problems continued, but we were drinking and eating. There was one steep

cross-slope section with a really icy step down, but Homie and I negotiated it

quickly. Homie and I got behind a pair of slower skiers who wouldnÕt move over

for us. It was too much effort to go around in the untracked powder, so we just

put up with it. Eventually, though, Homie couldnÕt stand it and zip around in

the powder, with me following. This was an exception. It seemed from here on

out everyone was really good about moving over to let a faster party pass,

including ourselves.

We just kept putting one ski in front of the other,

occasionally stopping briefly for a drink or to get some food or to pee. We

made the FriendÕs Hut station at 5:53 a.m. I never did actually see any hut,

nor did I at the Barnard Hut, but I assume it was nearby. There were some aid

station people out giving out cups of water and I downed a cup. I then headed

for the last section of trees to put on my mittens, my warmer hat, my neck

gaiter, and shell, and my full-length skins. Homie did likewise.

Above us there would be no protection from the wind. Star

Pass loomed very steeply above us. It was still dark, but we could see the

first signs of the approaching dawn. Before starting up the last climb Homie

said to me, ŌIÕm going to be slow. IÕm not feeling very well.Ķ We took it

pretty slow, but it was brutal at any speed. The wind had blown off any snow

that hadnÕt already turned to ice. That meant we were more sidestepping on our

edges than skinning up a steep slope. All the while the wind pounded us. I had

to concentrate hard on my edges so that I wouldnÕt slip down the hill and have

to regain the hard-fought altitude.

After topping the climb there is a high traverse across a

steep bowl to the actual pass. Here was another threesome of volunteers. They

were bundled to the hilt in what looked like Polar expedition suits. They stood

beside a serious Mountain Hardware dome tent. It was light now and I stopped

here to strip off my skins and wait for Homie. Below me was a precipitous drop,

but only for the first fifty vertical feet or so. Then it opened up into a

wonderful powder bowl. It was tracked by the racers before us, but the snow was

nice and made controlling our speed a lot easier.

I took my one and only fall of the race here and it was just

when I was stopping to look up the hill for Homie. I lost my balance and fell

backwards into the powder. Homie would join me in the powder a few times before

we got to the bottom. The other skiers in front of us were falling as well. One

team left behind one of their sleeping pads, probably not realizing it came

loose.

Homie and I skied across a flat meadow and on the other side

we found some race volunteers. They didnÕt have food or water for us, but they

did have a nice fire going. IÕd guess that some racers might be wet and cold

from the wind and falling in the powder, but not us. A few racers were huddled

by the fire and a volunteer asked if we wanted to stop and warm up our skins so

that they would stick better. You see, the glue on the backside of the skins

works best when it is warm. Most racers, ourselves included, would keep their

skins inside their jackets, to keep them warm. I put mine down inside my bibs

(it seems I keep everything in there).

We slapped on our skins on our skis and mine were barely

sticking on the tails. The volunteer asked me again if I wanted to warm them up

for 5 minutes by the fire. I asked Homie how his skins were doing and he

assured me that his were good. The volunteer rubbed my skin vigorously and

pressed it hard against my ski. This was some very nice assistance and I

thanked him for his support.

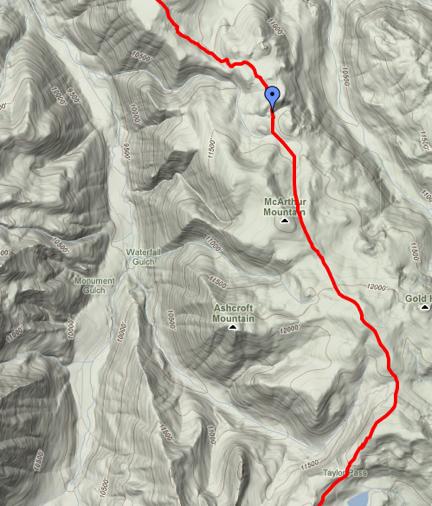

Figure 2: The blue mark indicates the

Friends Hut. The nasty climb up Star Pass is immediately following, then the

traverse to the actual pass and descent into the basin before starting up

towards Taylor Pass. You can see that the route climbs above Taylor Pass to the

northeast.

Homie and I started the long climb to Taylor Pass. This

climbed was gradual and stayed in the trees for a long time. We stopped a

couple of times for food or to de-frost our drink tubes and Homie even stopped

to pull on heavier gloves. Once we hit treeline, again, I kept thinking the

pass was imminent, but it always seemed to be around one more corner.

We eventually seemed to top out and there before us was a

great semi-flat expanse. I consulted with some other racers and decided to take

off my skins here, thinking I could kick and glide. Homie pulled off his skins

as well. While he had great traction, I did not. I struggled here and should

have put on my kicker skins immediately, but I kept thinking I was going to get

in some gliding. I never did. I herringboned up a couple of the rises and got

very tired doing so. I finally gave in and put on my kicker skins. By then I

was far behind Homie, but caught up quickly.

We still had gained the pass proper but when we did, we were

greeted with gale force winds. Much to our chagrin, the racecourse did not go

down the other side, but climbed the hill to the northeast. Here the winds were

so strong that all loose snow had been ripped away and only bare ice remained.

We both took off our skis for sections here as neither of our skis were getting

enough grip to keep us from being blown down the hill. I could only walk for

20-30 paces before stopping to rest, bracing myself against the raging wind.

At the summit, I didnÕt wait for Homie. I was very cold and

very miserable. Nothing could be accomplished in these conditions. I put my

skis back on and quickly skied down to the next saddle, at the base of another

substantial hill. I stopped here, now out of the worst of the wind, ate, drank,

and put my long skins back on for the climb. Homie joined me and followed suit.

We were pretty wasted at this point and desperately seeking

the solace of the Barnard Hut. It wasnÕt about to arrive quickly, though. We

climbed the big hill and descended again. Then we climbed up the slopes of

McArthur Mountain. A fellow racer told us the Barnard Hut was down beyond the

next rise. I pulled off my skins and rocketed down the slope and as far up the

other side as I could before stopping to re-skin. It seems like I took off my

skins and put them back on countless times. This got to be tiring.

At the top of this next rise, I stripped the skins once

again. From there I was able to ski downhill all the way to the Barnard Hut aid

station. This was the one and only real aid station in the race. You are

required to stay here for at least ten minutes. We stayed fifteen.

I had a couple of cups of Ramen noodles and some water. I

downed my second Ensure. Bob Wade, the owner of the Ute Mountaineer in Aspen

was working the aid station. He was very pleasant and very helpful. Just while

I was there he helped unfreeze at least four drinking tubes, including mine. He

filled my Camelback with hot water. He even waxed my skis with extra blue. He

described the rest of the course: ŌItÕs seven miles to Aspen ski area, but itÕs

a hard seven miles.Ķ He me that the wax would get me there except for one

20-minute climb where IÕd need full length skins. He was right and I followed

his advice.

The next seven miles last a long time, almost three hours,

IÕd guess. Homie wasnÕt very talkative here. WeÕd regroup whenever necessary.

There was one tricky, high-speed descent and then we came to the big climb. The

rest of the way to Aspen was along these snowmobile tracks with bumps or

whoop-dee-doos every few meters. These were very tiring and frustrating. I

passed two or three teams on this section as I skinned up. A couple of teams

were walking. Skinning was faster for me, it seemed.

At the top of the climb I stripped the skins for the last

time and waited for Homie. It wasnÕt the end of the climbing though. It seemed

it would never end and we trudged onwards, over each small climb. Another team told

me that the next climb was the last one where IÕd say, ŌDamn it!Ķ but it

wasnÕt. I herringboned up the one they indicated and there we met a number of

people camped out, cheering us on. One person told us it was a quarter mile to

Aspen, but it turned out being more than a mile still and included probably

three more small climbs.

Finally, we entered the ski area, at the very top of the

mountain, at the gondola. Race officials took our number and congratulated us.

I wasnÕt sure of the way down, but an Aspen Hospitality Skier volunteered to

guide us to the bottom. The easiest way down was a steep intermediate run.

Apparently Aspen doesnÕt have any snowcat trails.

We were quite the spectacle on the way down, with our packs

and our bib numbers. Countless people stopped to congratulate us and were

genuinely in awe of what we had done. Here we were finishing in the bottom half

of the race (top half of the starters) and getting such adulation. It was very

gratifying and surprising. How did all these skiers know what we were doing? I

guess this race gets some press in Aspen.

Homie was hurting a bit and struggled on the downhill ski,

but he had to be as relieved as I was to finally be done with the climbing.

When I entered this 40-mile race, I had naively assumed that it would be at

most 20 miles of climbing and then 20 miles of gliding downhill. Now, nearing

the finish, it felt like the race had 37 miles of climbing and three miles of

gliding. Nevertheless, I fully enjoyed this ski down. I zipped closely behind

my guide, parallel turning in her path and enjoying the nice, smooth snow.

We stopped to regroup four or five times and then Homie and

I skied across the finish line together. Before we had even come to a complete

stop, Sheri ran up to us holding her camera. She had been there since 11 a.m.

and now it was after 3 p.m. yet she was very excited for us. I was so glad to

see her and to finally take off my ski boots.

What a journey this had been, or, as the Grateful Dead said

it, ŌWhat a long, strange trip itÕs been.Ķ

We finished in 15h08m15s and were 66th place out

of 93 finishing teams. Not everyone made it, clearly. HereÕs a trip report about a pair that

didnÕt make it. The full results

are posted on the website. Fifty-three teams DNFed. That makes for a 64%

finishing rate.

The superstars of this event, like Mike Kloser, who won this

year for the fifth time, make the race seem reasonable. Even under the

horrendous wind conditions we had, he and his partner made it to Aspen in 9

hours and 15 minutes. My friend Charlie Nuttleman and his twin brother finished

in under ten hours. These times are deceptive. This wasnÕt their first time

trying this event. It was CharlieÕs sixth attempt, having various disasters in

previous attempts. Once he and his brother got severely hypothermic and race

personnel likely saved their lives. If alone, they might have died. And Charlie

is superhuman. He is one of the uber-athletes of Boulder like Dave Mackey,

Stefan Griebel, and Buzz Burrell. If you want to live, donÕt attempt what these

guys do. At least not without starting small and working up to your limit, will

likely be far, far below what you read about them doing. Before doing this

race, I thought CharlieÕs sub-10-hour goal to be an ambitious mark, but after

finishing the event, I canÕt even understand how he did it. How anyone can move

that fast and that continuously over such challenging terrain in such horrible

wind and stay warm and stay fueled baffles me. Yet, asking Charlie for beta on

how to do this race is like asking Hans Florine for beta on how to climb the

Nose. If I took eitherÕs advice, IÕd die. KirstenÕs advice was much more

relevant to my skill and fitness levels, yet I know now that I am not nearly

her equal at this race.

So much of this report is sprinkled with the phrase ŌI now

knowĶ or ŌnowĶ. Annoyingly repetitive, I know, but this race was eye opening. I

learned how incredibly ignorant I was. I was supremely humbled. I went into

this race wanting to later say Ōno big dealĶ. Now I bow before anyone who has

finished this race and stand in awe of anyone who goes back for more. I once

was blind, but now I seeÉ

Postscript: So, how do I compare this to the Lake

City 50 or to the Leadville 100 or even to climbing Buddha Temple in the Grand

Canyon? ItÕs hard to do, as they are all so different, but they are all

ultra-marathons. Grand Traverse is harder than Lake City, thatÕs for sure. ItÕs

way more adventurous and committing than Leadville, though takes only about

half the time. Yet, it is less adventurous, less committing, and shorter

(time-wise and vertical-wise) than climbing Buddha Temple. It all depends on

your skill set, I think, but IÕll say this. IÕm very proud to have finished

this race in my first try. And IÕm very proud to have partnered with HomieÉ