Are We Not Men?

October 11-14, 2001

Whenever things get difficult or plans get ambitious, Mark Hudon’s standard response is: “Are we not men!?” He doesn’t run from much in the climbing world. One of Mark’s favorite routes is the West Face of El Cap. He tried to climb it last year, but had severe partner problems. I’m a much weaker partner, but I can pull on gear with the best of them. Actually, that’s not even true. I can pull on gear, but certainly not with the best of them.

We decided on three days in the Valley. I really wanted to climb the Rostrum, as I hadn’t completed the entire route. Eventually, we thought it would be cool to do the Rostrum, West Face, and Astroman on successive days. When I tried to shed a little reality on the subject, Mark responded, “Are we not men!?” No, we were not. Mark is. I’m not. At least not that much of a man…

Mark Hudon wrote an article called “Long, Hard, and Free” where he expounded on the joys of freeing the big routes in Yosemite. These past three days I joined Mark in Yosemite to re-live some of his favorite routes. The last time he climbed any of these routes was the spring of 1983 (Fall of 1979 for the Rostrum).

Thursday: Hate Valley Hill

After two and a half hours to check in at the airport and get through security (my bags and I were selected for a random security check), my flight to Reno was uncrowded, smooth, and on time. I collected my gear and soon my friend “Doctor” John Black and his friend Ty Jones arrived to pick me up. John is a professor of computer science at UNR. Ty is one of his students.

We first headed to John’s house to watch a movie he made about himself and his new wife Sandra. John had just got married and I hadn’t ever met his wife. I still wouldn’t – at least until returning from Yosemite.

Afterwards, we changed to go running. John and I are both avid hill runners. We’d pass information back and forth via email about our latest runs. We each had hills in our area that were about two miles long with about 1200 vertical feet of climbing. Even with these similarities it was hard to compare times. Our only point of reference was the Upper Yosemite Falls Trail in Yosemite Valley. This past June I just barely broke his record for this course. From that I figured we were pretty evenly matched. We were both excited that I’d get to run his favorite hill.

Hate Valley Hill is what John calls his course up to a subsidiary summit of Peavine Hill. He has run it probably twenty times and whittled his time down from 30+ minutes to 25:49. His long-term goal was to break 25 minutes, but he hadn’t been running much lately and didn’t expect to be close to his record today. Ty’s best time was 28+ minutes and he didn’t expect to be close to that either. In contrast, I was in good hill running shape, setting a few personal records just before coming out.

After a brief warm-up, we gave Ty a 2.5-minute lead and then I gave John a 2.5-minute lead. I took off after them, but was confused as soon as I turned down the shooting range valley. There was an extra right turn here that John didn’t mention. It seemed a bit early and while I paused a bit to consider it, I didn’t think it was right. I headed further up the valley thinking that I’d just go cross-country if I had to.

I was surprised to catch and pass John before I had gone ten minutes. He was walking a steep section and I was still running – barely. Soon I was reduced to a walk due to the angle and the loose soil. I power hiked by Ty about a minute after I passed John and just before the halfway mark. Ty is a super nice, very positive guy and he encouraged me when I went by, as did John. John was even yelling out advice for me. How he could yell during this effort was beyond me. I couldn’t have even said a word.

I walked a good portion of the upper course, as it is quite steep. I ran whenever the trail flattened out. This entire run is on a steep, loose, dirt road. Actually, the first couple of minutes are now on a paved road. There are no trees and just scrub oak bushes loosely covering the surrounding terrain. It isn’t particularly aesthetic compared to the hills I run, but I was familiar with the pain.

I had a description of where the course ended, but wouldn’t know it until I passed it. I took splits at a couple of possible finish points, but kept going until I was sure. I finished in 21:51 and then continued another thirty seconds to the top of the hill. John’s time trial course ends a bit below this subsidiary summit since it turns off and descends along a trail that leads to the summit of Peavine. I’ll have to come back and try for the record on that one next. John owns the best known time at 1h29m??s.

I descended down to the bottom of the last hill and ran back up to the finish with John. He ran this whole last section and left me behind. I descended again to finish with Ty. John ran 28:12 while Ty ran just under 33 minutes. Prior to my attempt, but unknown to me, John predicted sub-22 minutes for me. Apparently he knows my capabilities pretty well.

John graciously lent me his truck for the long weekend and after dropping him and Ty off at school, I headed back to the airport to pick up Mark. After a late lunch at Mark’s favorite Mexican restaurant (he used to live in Reno), we headed for the Valley. We stopped once to get groceries and arrived at Hans Florine’s house around 7 p.m. Hans was there with his wife Jackie and their daughter Mariana, along with some roommates. He gave Mark and I the biggest room in the house and we started making plans for the next day.

Friday: The Rostrum

My friend Bruce “Dr. Offwidth” Bailey had been after me to climb the Rostrum for years. He claims it to be the greatest crack climb on earth. In this regard, he can’t be far off. This is a revered crack climb in the Valley and part of the triumvirate of big free climbs: North Face of the Rostrum (V, 5.11c), West Face of El Cap (VI, 5.11c) and Astroman (V, 5.11c)[1]. Bruce had particularly raved about the 8th pitch – a 5.11b-overhanging crack in tremendous position. Bruce claimed that if this pitch were located on the Cookie Cliff, it would “only” be rated 5.10d.

I had two previous experiences with the Rostrum. First, I had climbed the lower section of the route with Marty, who I met through John Black as it turns out. That day was hot and we bailed from the walk-off ledge. I only led one pitch that day and aided quite a bit of it. My favorite pitch was the beautiful 5.10b corner leading up to the walk-off ledge. This pitch was fun and challenging, but seemed considerably easier than the similarly rated Outer Limits on the Cookie Cliff. I was excited to lead this pitch.

The second experience was with the Loobster. I had wisely chickened out from doing the entire route. With the Loobster I would have had to lead everything and it would have taken days. We did a fifty-foot pitch over to the summit from the rim and I lowered down to check out the exit pitch. I climbed this nearly unprotected offwidth twice on toprope. I wanted to be confident enough to lead it. It went very well and I felt pretty solid on it. I used my head in a weird stemming maneuver to clear the initial roof, which was the crux of the pitch.

The alarm went off at 5 a.m. – mainly because I was too lazy to change it to 5:30 a.m. We spent a relaxing morning talking with Phil, who was off to do Royal Arches with a friend later. When we mentioned we were heading for the Rostrum, he commented on our early start. Had he known how slow “speed climber” Bill Wright is, there would have been no reason for the comment. We left the house right at 6 a.m. and fifteen minutes later were parked above the Rostrum.

It took us about an hour to start climbing after parking the car. In that time we hiked down the very steep gully to the walk-off ledge on the Rostrum, where Mark soloed out and left the pack with our water, extra clothes, food, #4 Camalot, and my jugging gear (for the last pitch). Then we had to do the four rappels down to the bottom of the Rostrum. I went first and completely missed the next set of anchors. The good news was that I just barely made a ledge just above the second set of anchors. Two more raps and we were on the ground.

The first pitch is rated 5.9 and that is probably accurate. The topo marks the crux down low but no one who climbs this pitch will feel that way. The real meat of this pitch is the “5.7” squeeze chimney just before the belay. This chimney, while mostly unprotected, goes pretty smoothly, albeit cramped, until the top, where a roof caps further progress. I struggled up here for quite awhile and got a bit gripped. The chimney is definitely wide enough to fall down inside. In desperation, I finally shoved a piece up underneath the roof and that gave me the confidence to twist around the other direction and finally escape the clutches of the roof. I was dripping with sweat and spent after only one pitch and by far the easiest pitch at that.

Mark raced up the pitch. The only trouble he had was burrowing in under the roof to remove the gear I left there. I sensed that Mark was a bit frustrated with my trouble in the chimney, as he sped into the lead without a pause. Later he would say that wasn’t the case at all. He was just excited to be leading a pitch.

Earlier, Mark told me a story about him making the 4th free ascent of Freestone (5.11c) on Geek Towers. Mark thinks out of every hundred successful Astroman parties only one would succeed on Freestone. He calls it “way bad ass.” On the crux 150-foot, 5.11c offwidth/fist pitch, Mark led it with only two pieces of gear - three successive runouts of fifty feet. He said he didn’t have the gear for the width. On the plus side, he paid no penalty for liebacking the offwidth. Normally this isn’t done because it is much less secure and harder to place gear. The advantage is that the climbing is usually a lot less work – at least over offwidth technique.

So, what does this the very interesting historical tidbit have to do with the Rostrum? Well, on the second pitch of the Rostrum there are two possibilities (actually there looks like there is a third possibility, but it looks harder and scary than the other options): a 5.11a thin crack or a thirty-foot lieback up a flake so thin it makes Wheat Thin (classic route on the Cookie Cliff at 5.10c) look like Texas Flake. Most people don’t climb this 5.10 flake because the crack it forms is 6” wide and you can’t place any gear. I figured Mark would just climb the 11a thin crack, but he glances up at the flake and just casual says, “I’ll just climb this flake here,” and even before he finishes the sentence, he is pulling up into it. He didn’t give a thought to the obvious fact that he’d have to go thirty feet before being able to place gear. Mark’s a great climber, but it still scared the crap out of me watching him get so far above gear on vertical climbing. Following this flake, I found it quite challenging and burly. I was unnerved by how thin the flake was and though I could break off the edge I was holding.

In Hans and my speed-climbing book (due out by the end of this month – rush out and get your copy now), Hans states, “between the two of us, we have climbed the Nose of El Cap 38 times.” This is about as accurate as saying “when Mark and I climbed together, between the two of us, runouts of 25 feet or more on 5.10 are common.”

Mark ran the second and third pitches together. Actually, it depends on how you break up the bottom of this route. The party after us did three pitches to the ledge also, but broke it up differently than we did. Nevertheless, the topo calls for four pitches to the ledge. Above the flake, an awkward fist crack / stemming section leads to a good rest at an alternate belay. Next is a difficult (10b?), but short, lieback section turns into a long, continuous 5.9 hand crack. On this 190-foot pitch, Mark placed three pieces of gear, and clipped two fixed pieces – one of which was the alternate belay.

Next was the real gem of the lower section. A slippery undercling, which is the technical crux of the pitch is used to gain entry to the beautiful corner system with a nice hand crack. The climbing is continuous, but not really that bad – as the corner isn’t vertical. At the top of the dihedral there is a short vertical section that I surmounted with some fingerlocks and positive face holds. This ends on the walk-off ledge.

We were both established on the walk-off ledge by 9 a.m. Four pitches down and just five to go. We knew this was deceiving though, as the meat of the route lay above us. In fact, the night before Hans had tried to convince us to forego the rappels to the base and just lower down a rope length from this ledge and top rope the last 200 feet below, call it good, and head up from there.

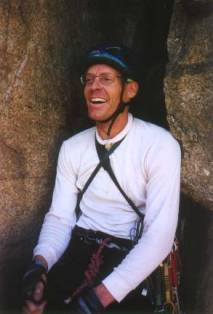

Photo 1: Relaxing at the top of the 11c pitch.

The technical crux of the route is right off this ledge. The climbing is very sustained fingerlocks with very limited and technical footholds. Basically, you need to be able to stand on minute irregularities on the face to the left of the crack and try to push on the edges of the crack with your right foot. Mark looked very solid on this section and then cruised the next section, which is also 5.11 but easier. After thirty feet of very difficult climbing, Mark did a delicate traverse to the left and into a steep corner. A hundred feet of continuous, steep 5.9 crack climbing deposited him on a good ledge.

Following this pitch, I had my troubles. While I didn’t use any aid to ascend this pitch, I fell off it five or six times. The fingerlocks actually felt pretty good to me, but the wall was too steep and my footwork lacking. I could hang on, but letting go to move my hands up was too much for me. I’d gain a few feet at the time and then fall off – losing more altitude than I had gained due to rope stretch. I kept at it, trying to use my feet better and pushing hard, blooding my fingers in the process.

Eventually I made the top of the fingercrack and moved left into the dihedral. The long dihedral further wore me down and I arrived at the belay pretty exhausted. It was going to be a tough struggle to the top. There were four pitches to go – two leads for me. I was already thinking about abdicating my last lead, the 5.11b enduro pitch.

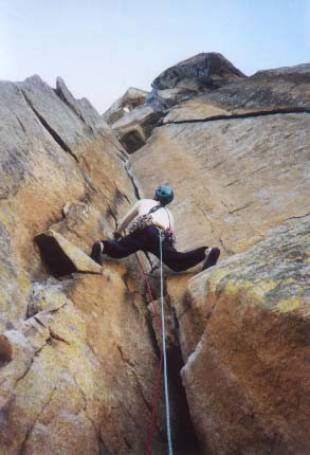

Photo 2: Leading up the 10d corner pitch, just above the crux pitch

I rested a bit at the belay and took my time re-racking. The pitch above looked like a classic, Yosemite crack pitch. A dearth of footholds or ledges meant that resting would be difficult, but since it was in a corner I knew there would be stemming possibilities. Despite this, once I got pumped and above gear, my mind locked up and I failed to press into an obvious stem and tried to jam in a cam from an awkward position. Instead, I took the plunge and hung on the rope.

Mark yelled up some good advice about the now-obvious stem. I climbed back up and pressed into the stem. Sure enough, it worked fine and I plugged in some gear. I continued up the roof at the top of the dihedral. Here I underclung out to the left, clipped a fixed piece, and slumped back onto the rope. I knew this section was the 10d crux and I probably psyched myself out a bit. I climbed up a bit higher, placed another piece and hung again. The rest of the way there wouldn’t be much opportunity for placing gear and I rested before firing up the final fifteen feet to the belay.

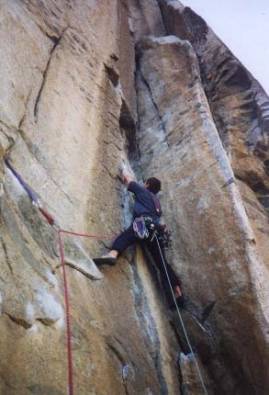

Photo 3: Mark leading the 5.10 offwidth pitch. He has just finished the 10c face section (the only face climbing on the route). The offwidth doesn't start for another thirty feet.

Mark fired up the pitch and back into the lead. The next pitch traverses back right into a left-facing corner. For the next pitch and a half, our route and Blind Faith, a continuous offwidth climb, would overlap. Yes, that means we’d be climbing some offwidth. In stark contrast to what was to come, this pitch started with a delicate, thin, fifteen-foot face traverse – the only face climbing on the route.

After the traverse the climbing was steep and demanding, but not offwidth…yet. At the start of offwidth, it is possible to stem off an edge. Eventually they become too far apart and one must commit to the offwidth. Mark would later call this section the most difficult of the climb. It is just a classic offwidth/flare grunt where moving quickly is out of the question. Mark left our single #4 Camalot low on the pitch, then clipped the bolt further up, and had to run out the final thirty feet of offwidth grunting. Most teams either carry two large pieces or walk the #4 Camalot up most of the pitch.

Following this pitch, I nearly fell off on the 10c face section and then struggled mightily on the offwidth, but maintained good technique for longer than I usually do. I even did a hand stack at the crux – the third or fourth of my climbing career. I arrived at the belay fully spent, but pleased to climb the pitch clean. It was my first clean pitch since the walk-off ledge.

I was tired and the next pitch looked brutal. I asked Mark, “Is it ridiculous for me to lead this pitch?” He echoed back Dr. OW’s words, “It’s only 10d, Bill. You’ll do fine.” I took the rack and headed up, almost immediately whining about the protection possibilities, lack of rest, and confusion about the best way to approach the pitch.

Photo 4: A climber near the top of the "enduro" 11b pitch.

Nevertheless, I managed to climb a third of the way up the pitch before it got ugly. I then hung on some gear and whined some more. I climbed up to the “Tooth” and underclung up to the overhanging hand crack. I placed a piece here and hung again. The next section has a wide offwidth section that needs to be spanned via a huge reach from a great hand jam to a straight-up, flared jam at the top of the pod. This is a technical and super burly move and it was too much for me. I fell off it a couple of times before hauling up the #4 Camalot and aiding by this section.

Above the climbing was continuous and burly. I got into the beautiful stem that Dr. OW had raved so long and hard about. I was mentally and physically spent and just needed to make the belay at this point. Above was a wide crack and I wasn’t confident enough to run it out to a hand jam. I lowered down and pulled our single #3 Camalot. Armed with this piece, I aided the rest of the way to the top. It was pitiful, but I got to the belay.

Mark followed and confirmed it to be a solid 5.11b pitch and definitely no “5.10d.” This was good to hear. This pitch seems nearly as hard as the 11c pitch below. It just depends on your strengths, I guess. This is not a super technical pitch, but it is very continuous and very burly – just the type of pitch the good doctor loves.

Mark geared and started up the intimidating Rostrum roof. This roof starts right from the belay and is completely horizontal for four feet or so. The crack that splits the roof looks to be off-fingers, but Hans claims the locks are good – at least until you turn the lip. The climbing looked nearly impossible and I was really interested to see how Mark was going to hang completely from that crack. I felt there was no way to keep the feet on the rock while turning this roof.

Mark hand traversed a few feet left and placed a couple of pieces. The Alien finish goes up more directly from the belay, but the regular North Face finish traverses six feet left. Both are rated 5.12b and I’m not aware of the qualities that would recommend one over the other. For the first time I saw Mark balk. Heck, he might even have blanched. He climbed back to the belay to reconsider and then back out. He then decided, quite abruptly, that he didn’t want to do it. It required a deadpoint to fingerlock on a horizontal roof and it just didn’t seem like fun.

Mark bailed out the Blind Faith exit (the 10a offwidth that most people take and the one I had toproped with the Loobster) so fast, that he almost forgot to bring the #4 Camalot with him. This would be the only piece of protection he’d get on the entire eighty-foot pitch. Nevertheless, he moved quickly. This pitch isn’t nearly as hard as the lower 10a offwidth. The crux is turning the roof at the bottom. I told Mark as he headed out that I used a head jam to surmount this section. He scoffed at such a ridiculous, unaesthetic move and moved around the corner out of site. On the summit, he would sheepishly admit to using his head. It really comes in handy for turning this roof. The crack through the roof is offwidth and while your legs are below the roof, you can’t get them in the crack. I climb it by liebacking off the crack and getting my feet up on some holds well to the left. This puts me in nearly a horizontal position. By bracing my head against the wall, I can shuffle up my hands and thereby move my feet over to the crack. The #4 Camalot protects this move and then it can be moved up a bit, but it soon becomes too wide and one has to grunt up the 5.9 offwidth for about fifty more feet – with no gear. This sounds frightful and I haven’t led it, but it isn’t quite as horrible as it sounds since there are a couple of face holds were you could get a good rest. I think I would lead this pitch, but it would be scary and serious. I felt solid following it, though, and I don’t think I’d fall off of it.

Photo 5:

Mark starting up the Rostrum roof, Photo

6: Peter Croft at

the same point on

before deciding against it. the

Rostrum roof.

We relaxed on top for a bit and took a summit photo. The Rostrum is a semi-detached pillar and to get off of it, we needed to do a short rappel into a notch and then climb fifty feet out on 5.6 climbing. As we were rappelling, a guy appeared on the other side. He was there to walk the sixty-foot slack line set up across the 1000-foot chasm that existed between the Rostrum and the rim. His name was Jason and he was quite friendly. He asked up if we wanted to smoke a bowl of weed with him. Mark wanted to jump all over that, but when I mentioned I was trying to cut back, he joined me in a show of solidarity. Jason walked a practice slack line set up just a few feet above the ground and then psyched up for this walk. The master slacker-liner, Dean Potter, had placed the line and a few days ago Dean had walked this line without a tether! That means if he loses his balance, the result is death. Okay, so it is possible to grab the line when falling, but many miss it and fall onto their tether.

Jason walked it clear the Rostrum, let out a yell of relief and then walked it back! We photographed him with our camera and with his. Mark shot 14 of Jason with his camera and he was quite thankful. Jason said he’s never coming back to this line. He did it! Jason, like everyone else including Potter most of the time, walks the line with a swami belt around his waist that is attached to two lines, which in turn are attached to two rappel rings that encircle the slack line. This way a fall, though terrifying, will not be fatal.

On the hike out, Mark was telling me that he wasn’t upset waiting for me to aid my way up the “enduro” pitch. He said, “It was a great day in Yosemite. I wasn’t too hot or too cold. I knew you’d finish some year.” I responded, “Hey, I was building character up there!” After some reflection, I added, “Now I know what you are thinking. You’re thinking, ‘But Bill, you already have so much character.’ That’s true, but I always like to have some in reserve.” After this route, I’ve got so much character built up that I can hardly get off the ground.

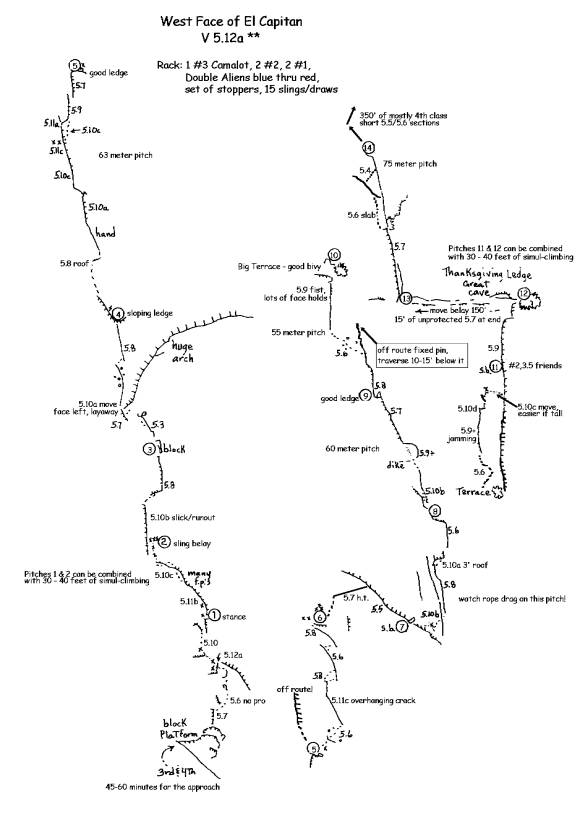

Saturday: West Face of El Capitan

I had climbed the West Face last year with Hans. We did a speed ascent – meaning we grabbed gear on the harder pitches – and completed the route in 6h20m. Mark, like most climbers, isn’t a speed climber per se. He climbs quickly and efficiently and that naturally leads to reasonably fast times, but that isn’t his goal. His goal is free climbing. I wanted to free more of the route also, but a clean ascent was well beyond my reach.

The Rostrum had taken a lot out of me, but we finished early enough in the day to plan for the West Face the next day. We’d be feeling the effects of this decision later in the day. Any time you climb El Capitan – house to house – in a day, it is a significant undertaking. You still have 3000 vertical feet to ascend and descend – most of it quite technical. The night before we talked about our plans with Hans. He scolded us for climbing with a second line and hauling a pack with water, food, extra clothes, etc. Hans believes the second should be doing some work and wearing the pack. I was pretty much swayed, but Mark was adamant that he didn’t want to wear the pack. Considering he’d be leading most of the route, this amounted to Mark hauling the pack for me. Mark was guiding me pro bono.

We were up at 4:30 a.m., out the door at 5, and hiking by 5:30 a.m. Hans, who times everything including how long his 10-month old daughter naps, asked us if we’d be going for the record approach time (44 minutes). This guy is over the top, and that is coming from a guy who times just about everything. We hiked completely via headlamps and got to the base at 6:30

After the necessary preparations, Mark started the first lead just after 7 a.m. The guidebook rates this pitch 5.11b, but Tom Issacson calls it 5.12a and that seems more accurate. Mark cruised the crux and felt it was more like 5.11c. Following this pitch, I couldn’t detect a single useable hold at the crux. It isn’t that steep here, but is quite smooth and featureless. With a couple of judicious pulls on draws, once at the crux another a bit higher, I dispatched the pitch and Mark started the next pitch, also 5.11.

The second pitch is more sustained and involves a creative mixture of delicate footwork with crimps, liebacks, palming and underclinging. Mark showed more effort on this section, but moved steadily through it and then through equally cool, but easier at 5.10, climbing up and left to the belay. I briefly thought about trying harder to free this section, but quickly realized that this route was too long and too hard for such ill-advised heroics. I save my effort for the 5.10 pitches. It would be fun to come back with only the intention of working to free the first two pitches.

The third pitch is 10b and would normally be my lead, but it is very slick and a bit runout. It climbs an extremely polished corner via stemming and liebacking. Hans took this lead on our ascent and, while I didn’t fall then, I once again thought of the size of the route and deferred to Mark. He promptly took a fifteen-foot fall. “Slick, yes. I agree,” said Mark as he swarmed back up the rope and right back into the lead. Fifteen feet above the piece that held the fall, he placed a blue Alien, commenting, “With that fall in mind, I’ll place another piece.” I followed cleanly – my first of the route – and led the fourth pitch. This pitch has a tricky 10b move on it, but I was familiar with it. With Hans I took about ten minutes to psyche up for this move, but today I immediately committed to it and found it pretty hard. I slapped once up an arête and barely pulled it off. Above is great, interesting 5.8 climbing. In fact, many of the pitches on this route have really quality moderate climbing on them.

Mark went back into the lead again as we had two more 5.11 pitches to deal with. The next pitch is probably the best on the route. It starts with 30-40 feet of unprotected 5.8 face climbing to a fixed nut. Then you clear a small roof on good holds, but it is quite steep here. Above the climbing gets progressively harder. Now the climbing follows a crack with fingerlocks, liebacks, and the occasional hand jam. To go from the sloping belay at the end of the fourth pitch to the next ledge, requires 65 meters of rope or, in our case, 5 meters of simul-climbing. I unclipped from the belay and moved up, pulling the bag with me. Initially the climbing is easy and this isn’t any trouble. I set the bag on a small ledge and moved up about twenty above the belay before Mark started to haul the bag – the signal that he was at the next belay. I freed the pitch until four feet below the intermediate hanging belay. The crux 11c moves are here and I pulled on a draw and stepped in the belay slings before freeing the next 10c section up to the belay ledge.

Next up was the physical crux of the route: an overhanging 11c crack. This crack was unlike most cracks associated with Yosemite. It is heavily crusted in quartz crystals and is incipient. Judging by Mark’s breathing, this crack proved challenging to him also. Halfway up the crack, at a large hold, Mark hung straight-armed until his breathing returned to normal. Then he continued up the tricky section and over the top bulge. With Hans, I had to hang on the rope a couple of times before getting up this crack and that was still pulling on the gear. I warned Mark about this and he was surprised when I was topping out on it without ever weighting his belay. He was about to praise my effort when he noticed my handhold was a quickdraw. I pulled on four pieces to get over this section.

I led the next pitch, which ends at the same elevation as it starts. The pitch goes up and right and then a 5.7 hand traverse leads to a 5.5 gully/slot/ledge thing which goes down and further right. Mark tied the bag in short and I hauled it across. Next up is the 5.10b face section. With Hans, I chickened out on 5.10 section, but found a way around it by using a tension traverse to a crack. This time, once again in the interest of time and thinking that I’d procrastinate about committing to the moves, Mark led the pitch. This pitch also goes over a 3-foot 10a/b roof, but Mark found it was possible to climb around the right side at maybe 5.9. This is about a 50-meter pitch. From here, two 60-meter pitches will get you to a big ledge. I led the first one, 5.10b, and Mark led the second one, 5.9. After falling off the start of my lead – and back to the belay – I found a better sequence and led cleanly to the belay. The pack came up surprisingly easy. Mark wasn’t so lucky on his pitch.

From the big ledge it is 240 feet to Thanksgiving Ledge and the end of the hard climbing. This is normally done as two pitches at 5.10d and 5.9. This involves an awkward, hanging belay in a corner system and this is what Hans and I did. Mark and I knew time was short. We had to be starting out descent by 4:30 p.m. or we’d be caught on a highly technical descent without any lights. We had foolish forgotten to throw in my tiny Tikka headlamp – just in case. We were now in a race against darkness. Losing would mean spending a night in the gully. We had two hours to climb seven pitches – only two of which were harder than 5.7. With this in mind, we decided that Mark would try to link the two pitches to Thanksgiving Ledge.

Mark climbed up the lower 5.6 section and then into the crystal-coated, awkward crack that led up vertical to a difficult reach to a jug. Above here he was out of site, but yelled down a few questions about where to make the traverse into the corner. This is supposedly a 10c move, but it isn’t that hard for someone my height. It is delicate and involves a long reach and I could fall off of it, but it isn’t very physical, is only one move, and is super well protected by a bolt.

Eventually, all the rope ran out. I put our haulbag on my back (we had previously rigged it as a backpack, anticipating this situation). I climbed completely up the easy section and still the rope pulled on me. I cleaned the #2 Camalot at the start of the 5.9 section and moved up five or ten feet before refusing to go any further. I re-placed the piece and clipped into it. If I fell while simul-climbing with Mark, it could kill him. It is simply not allowed. What were the options? Mark wouldn’t be able to move up. He might have to downclimb. He might fall while downclimbing. All of these are much, much better options than for me to fall while Mark is above gear. If he falls off, the rope will give him a dynamic catch by stretching. Certainly he could get injured in a fall, but if I fall off, Mark will be pulled directly to the last piece and there will be no stretch in the system that stops him. The injuries in this case could be catastrophic. Having done a lot of simul-climbing and a lot of thinking about this situation, I knew all this instinctively. I couldn’t go on and risk that for him. I felt the changes of me falling off on this awkward section, while wearing the pack, were just too high to risk death. I wondered what would happen next.

Much to my relief, the pack was soon being pulled off my back. That meant that Mark was anchored. Mark had just been able to make Thanksgiving Ledge and had to anchor himself with the extra slack on the haul line. Soon I was climbing again. I yarded on the fixed sling at the top of the crack to reach the jug and was soon on the slab above. The pack was lying on the slab a ways above me. I got to a good stance and yelled up for Mark to haul the pack. He was wasted from the length of the climb and the exertion of such a long pitch. He had no desire to haul the pack. Mark was probably thinking, “You get your ass up here and haul the pack yourself, you pansy.” I wouldn’t blame him for these thoughts, but I also didn’t want the pack to get stuck and felt it should be hauled before the second climbs by it. It probably would have come up easily.

The rest of this pitch is physical 5.9 crack climbing in a corner that leans at an awkward angle. There are quite a few rests though. I was tired when I pulled onto the ledge, but knew there was 400-500 feet to go. The climbing from here on up was 5.7 at worst and Mark wanted me to take lead. He said, “I just want to follow on a nice tight rope.” He threw on the pack and I started up. We mostly simul-climbed to the top, but I stopped twice to belay him up and to pull up both ropes. Once I was dragging the full 400 feet of rope behind me (lead and haul line), I had so much drag that I could only continue for another hundred feet.

I led us directly to the start of Hans’ psycho rappel route. We regretted our decision to descend this way, but we were committed. The rest of our gear, including my shoes, was at the base of the route. Our race against time continued. It was 4:30 p.m. and would be quite dark at 6:30 p.m. and pitch dark at 7:00 p.m. The “record” for this descent was 1.5 hours. I figured we’d need at least 2 hours and probably more in our current state.

This descent is the scariest I have ever done. The really dumb part is that I have now done it twice. The issue is the rappel anchors and the distance between them. Hans put in crappy anchors of bashed in stoppers and small hexes (some of which are loose) and old pins. They are connected together with old bits of perlon and spaced out by 31 meters. Why 31 meters? Well, if you asked Hans he say the anchors are 29.5 meters apart. Who’s right depends on the exact length of your “60-meter” rope. Mammut apparently is known for cutting their ropes a bit short. Woe to the person who descends this way with a Mammut. Oh yes, we had a Mammut[2] – though Mark claims he measured it out to be exactly 200 feet.

We did four rappels down to the manzanita ledge and bushwhacked across, down, and through over to the next set of five rappels – all scary, save one that had two beautiful bolts and double rappel rings. This anchor sticks out like a sore thumb. We were now in the El Cap Gully, which is 3rd through 5th class. The whole descent, from the summit to our packs, is two thousand vertical feet and most of that is quite technical. We downclimbed a couple of 5th class cliffs and finally reached the last barrier just as it was getting too dark to see. We threw the rope around a tree and hoped that it reached the ground – we couldn’t see the bottom. I rapped down into the darkness. Thankfully it reached easy terrain and I was soon back at the packs and digging for my headlamp. It was 6:58 p.m.

There was no need for haste now. It was pitch dark and we were tired. We lay down with our packs and ate and drank to our hearts content. We found a couple of abandoned water bottles at the base of this route, so water flowed generously. The descent back to the car was slow, tedious, and serious in spots, but we had lights and took care. We were back at the car at 8:45 p.m. and Mark’s biggest concern: “I sure hope that grocery store stays open until 9. We need beer!”

Off we drove, arriving with only a minute to spare. Five minutes away from the store, with beer in our possession and headed for Hans’ house, Mark realizes that the beer he bought was not twist off. He urged me to pull over and shut off the car. He needed the key to open his beer. With that problem solved we continued on our way. Mark regaled me with stories of him opening beer bottles with the most ridiculous items. He claimed to be able to open a bottle with a tennis shoe! Five minutes from Hans’ house, Mark has finished his first beer and can’t wait for a second. We pull over and repeat the procedure to open the second beer. This guy has earned it and I’m more than happy to oblige.

Mark Hudon thinks everyone should have “events” in their lives. Not just the things you do every day: going to work, playing with the kids, playing tennis or softball or whatever. These are great and necessary things, but they aren’t “events.” Many people (most?) go through life with few “events.” Climbing the West Face was an event for us.

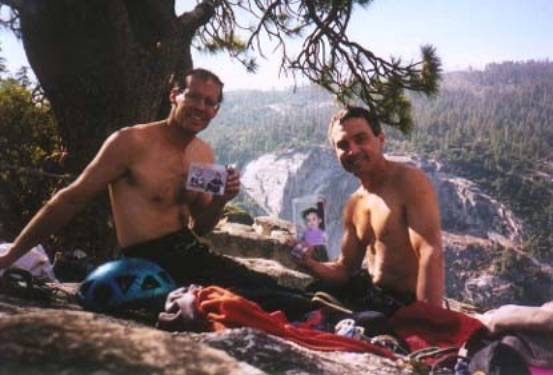

Photo 7: Hardmen or Just Dads? You decide...

Sunday: El Cap Lieback

We had previously entertained thought of climbing the Nabisco Wall (3 pitches, 5.11a) today, but after the previous day’s thrashing we opted for the classic Yosemite rest day: kicking back in El Cap Meadow and watching the climbers. We spotted teams on the Nose (only one party!), New Dawn, South Seas, P.O. Wall, Mescalito, Zodiac, and False Shield. Hans said the rumor was that Dean Potter and Tim O’Neill were going to try and break the Nose speed record. Of course, we were hoping to see a pair racing up the route, but alas were not that lucky. They went for it the following day.

On October 15th, Boulder local Tim O'Neill and Dean Potter set a new record for climbing the Nose on El Capitan in Yosemite Valley. This route is 3000+ feet of vertical granite. It is normally climbed as 34 pitches of 5.11/A1 over 3 to 5 days. These two guys raced up it in 3 hours and 59 minutes! The previous fastest time was 4h22m by Hans Florine and Peter Croft. Earlier this year Hans tried to break the record with Estes Park climber Tommy Caldwell and they did 4h31m. This was the longest standing speed record in Yosemite at 9 years old. Hans is already plotting an attempt later this month.

That kind of speed is out of my reach, but I really wanted to watch it. We packed up headed back to Reno around 2 p.m. and arrived around 6:30 p.m. We took John and his wife Sandra out to dinner and then I stayed up late talking with John until 12:30 a.m. I got up three hours later and headed for the airport with Mark. He had a 6 a.m. departure and we wanted to be there two hours early.

We had a great, but all too quick, trip. I can’t wait to return.

Table 1: Mark Hudon's history with El Capitan

|

Route |

Partner |

Date |

Results |

Comments |

|

Triple Direct |

Eric Sanford |

Spring 1974 |

Attempt |

rain |

|

The Salathe Wall |

Peter Cole |

Spring 1974 |

4 days w/4 pitches fixed |

|

|

The North America Wall |

Rainsford |

Fall 1975 |

Attempt |

Mark re-broke ankle |

|

The Dawn Wall |

Will Miller |

Spring 1976 |

Attempt |

bad weather report (false);

scared |

|

The Nose |

Max Jones |

Spring 1976 |

2.5 days from Sickle Ledge |

|

|

The Dawn Wall |

Peter Cole, Rainsford |

Fall 1976 |

Tower start |

3rd ascent |

|

The Magic Mushroom |

Peter Cole, Mark Ritchie |

Spring 1977 |

|

3rd ascent |

|

The North America Wall |

Eric Sanford |

Spring 1977 |

|

|

|

The Mescalito |

Max Jones |

Fall 1977 |

|

5th ascent |

|

The Zodiac |

Max Jones |

Fall 1977 |

|

|

|

The Pacific Ocean Wall |

Max Jones |

Spring 1978 |

Attempt |

Mark dropped a rock on his

finger |

|

The Salathe Wall |

Max Jones |

Spring 1979 |

4.5 days from Heart Ledge |

|

|

The West Face |

Max Jones |

Spring 1979 |

7 hours w/2 pitches fixed |

2nd free ascent |

|

The Nose |

Max Jones |

Fall 1979 |

2.5 days w/nothing fixed |

Strict lead and follow – no

jugging! |

|

The Tangerine Trip |

Rainsford |

Fall 1979 |

|

|

|

The Horse Chute |

Max Jones, Gary Allan |

Spring 1981(?) |

Attempt |

Bad weather |

|

The Shield |

Eric Barrett |

Spring 1983(?) |

Attempt |

Mark freaked out |

|

The West Face |

Shelley Presson |

Summer 1985 |

9 hours w/2 pitches fixed |

Mark led the whole route |

|

The South Seas |

Rainsford |

Spring 1986 |

Attempt |

Mark freaked out I gave

away all my big wall gear after this attempt. |

|

The West Face |

Gary Allan |

Spring 2011 |

Attempt |

Gary was overweight, shoes

sucked, food poisoning, party ahead of us... |

|

The West Face |

Bill Wright |

Fall 2001 |

9.5 hours from the ground |

|

Table 2: Bill Wright's history with El Capitan

|

Route |

Partner |

Date |

Results |

Comments |

|

East Buttress |

Giles Bouchard |

1991 |

12 hours car-to-car |

I led the entire route. |

|

The Nose |

Loobster |

May 1993 |

3.5 days |

Fixed to Sickle on the

first day, then slept on El Cap Tower and Camp 5. |

|

Salathe |

Hardly Manson |

June 1999 |

5 days |

We were a day slower than

planned due to crowds |

|

East Buttress |

John Black |

June 2000 |

7 hours car-to-car |

I led the entire route. We

then climbed Snake Dike to complete the Poor Man’s Link-Up, all in 15 hours. |

|

West Face |

Hans Florine |

June 2000 |

6h20m for route; 10 hours

car-to-car |

This was done two days

after the PMLU (see above). My first big wall speed climb. I led half the

pitches, but the easiest ones. |

|

West Face |

Mark Hudon |

October 2001 |

9.5 hours on route; 15

hours car-to-car. |

I freed a bit more this

time, but also followed more. Mark freed the entire route. |

|

The Nose |

Hardly Manson |

June 2002 |

21 hours and 55 minutes for

the ascent. |

Nose in a day! We started

at 4 a.m. and topped out just before 2 a.m. We rested, ate, and froze on top

until 5:30 a.m. and then descended. I immediately climbed Nutcracker on

Manure Pile Buttress with Opie and Toolman – an El Cap link-up! |

|

East Buttress |

Opie, Toolman |

June 2002 |

Casual and fun. Roundtrip

in around ten hours. |

The day after descending

from NIAD. |

|

Salathe |

Jim Herson |

June 2002 |

15 hours with Jim leading

every pitch and freeing it entirely until high on the headwall |

Four days after descending

from NIAD and my third ascent of El Cap in the past six days. I free climbed

7 or 8 pitches and jugged the rest of the route. We descended entirely in the

dark and got down around 11 p.m. |