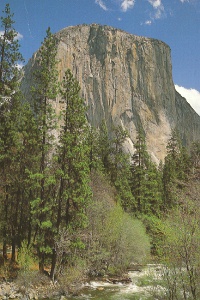

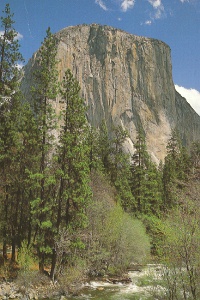

Southwest Face of El Capitan - Salathé climbs the middle of this

wall.

Southwest Face of El Capitan - Salathé climbs the middle of this

wall.Salathé Wall

June 5th - 10th, 1999

I had always viewed climbing El Capitan in Yosemite Valley as the pinnacle of my rock climbing career. In 1991, the Loobster and I climbed the Nose Route on El Cap and it went very smooth. I knew I'd be back though. I also have a habit of pursuing the "50 Classic Climbs" of North America. These 50 climbs include not only the Nose, but also the Salathé Wall route on the southwest face of El Cap. The Salathé is the longest route on El Cap (Free Rider, which takes a variation of the Salathé to avoid the overhanging headwall near the top, is equally as long. Also there exists a girdle traverse of El Cap that was done recently by Chris McNamara, which is 70+ pitches long).

Southwest Face of El Capitan - Salathé climbs the middle of this

wall.

Southwest Face of El Capitan - Salathé climbs the middle of this

wall.

The Salathé was the second route climbed on El Cap. The climb was done largely in response to the siege tactics involved in the first ascent of the Nose. Royal Robbins, the undisputed ruler of the Yosemite climbing elite, teamed up with Chuck Pratt and Tom Frost for the Salathé. Still unwilling to risk a completely alpine-style ascent, the threesome reconnoitered the lower third of the route and fixed ropes from their highpoint, at the base of the famous Heart feature, to the ground. From here they blasted off into the unknown - cutting their umbilical cord to the ground. This was perhaps the most audacious move in American rock climbing. Many days later they topped out on what has been called the greatest pure rock route in the world. Robbins would later call it the "finest rock climb in the world." This was my objective.

By virtue of its history, its place in Fifty Classic Climbs of North America, and its clean climbing (by this I mean it can be climbed without using a hammer), the Salathé has long been on my list of climbs to do, but for a variety of reasons had not actually been scheduled. Scheduling is one of the cruxes in climbing a big wall. Taking that first step on a long journey can be the most difficult. Finding a reliable, compatible partner with which to commit is the most important step. I found this partner in my friend Hardly Manson.

Hardly and I had climbed together many years ago - in fact, I taught him how to climb. Back then we even planned an ascent of Half Dome together, but illness stymied that adventure. There was a long hiatus in our climbing partnership until Hardly moved to Boulder, Colorado. We started adventuring again. His longtime travel/life partner Judy was such a good climber that he rarely needed me as a ropemate and we frequently did climbs together, but with other partners. At a slideshow eight months ago I casually mentioned my desire to climb the Salathé and Hardly jumped at the chance. He recognized the opportunity to learn a whole new facet of climbing, for he had not done a big wall climb before nor had he even aid climbed. I was skeptical whether he would enjoy it. Hardly is a very good free climber and I thought the slow, methodical nature of aid climbing and the laborious hauling would sour him. I was wrong. Climbing El Cap is a lot of just plain hard work and it takes a long time for average climbers such as myself, but above all, climbing El Cap is a big adventure. This was all Hardly needed. The rest were details to be worked out.

Hardly was excited about doing a really big route and he did his homework. He had never done any aid climbing before. He asked a lot of questions and then went out and purchased his aid gear. At first he practiced solo with a toprope. Then he did some more with his girlfriend, Judy. We planned a week long trip to Zion for more aid practice. This trip was largely washed out because of the rain, but we did get up the Touchstone Wall and half of Spaceshot. It would have to do.

Over the nine years I lived in San Jose, I'd climbed most of the major structures in Yosemite Valley including El Cap via the Nose route in 1991. I'd climbed the Nose with the Loobster, but he didn't feel he'd be in shape for the Salathé and declined an invitation to join us. In early 1994 I moved to Boulder, Colorado and had only done one major route in Yosemite since (North Face of East Quarter Dome). I wondered if I could still climb the big walls of Yosemite and whether or not I'd freeze up on the intimidating, overhanging headwall of the Salathé. This headwall starts with pitch 29 and has 2700 feet of overhanging air underneath it. I knew I wouldn't freak out, but I was worried that I'd become overly cautious and decline leads or move too slowly.

Joining us for the week long trip to Yosemite was Hardly's girlfriend, Judy, and our friend John "Homie" Prater. Homie had been climbing for a few years and very excited to see the rock climbing garden of Eden. We left in my RV after work on Friday at 5 p.m. from Golden, Colorado. We were hiking into El Cap a little past noon the next day! This included an hour-long breakfast stop at Lembert Dome! This was probably our most significant feat of the trip. With four drivers and plenty of room for everyone to sleep, the drive isn't too bad. About five hours of driving per person. Because of this we arrived in a well-rested condition and could immediately start climbing. We were also lucky enough to arrive just after a storm that sent many parties into retreat and even caused the rescue of a couple.

With just cragging packs, we arrived at the base of the Salathé to find a party of three gearing up. Damn! They had probably arrived no more than fifteen minutes ahead of us. "We shouldn't have stopped for breakfast in Toulumne!" I moaned. I cautiously queried one of them, who looked vaguely familiar, about their plans.

"Are you doing the entire Salathé?"

"Yes."

"Where are you planning on biving?"

"Hollow Flake or Lung Ledge tomorrow; the Spire the next day; and then Long Ledge or off on the next day"

"If you're only going from Hollow Flake to the Spire one day, then you'll never be fast enough to get off the next day," I lectured.

"We can do amazing things," said the tall, lean climber.

"Yeah, right," I thought. I've heard such claims before. "Darn," I said, "Those were our plans also."

"Well, these things tend to work themselves out," he said.

We moved past a bit to climb Pine Line (5.7). This is an alternate start to the Nose. It avoids the 200 feet of 3rd/4th class with easy hiking and one 100-foot 5.7 pitch. I had done this route a long time ago and thought it would be fun for our two Valley virgins: Homie and Judy. Plus it allowed us to keep a close eye on the queue for the Salathé. In fact, our two biggest worries about climbing the Salathé were the weather and the crowds. The weather looked like it would treat us well, but already we were probably going to have to delay our plans by a day due to a route queue. Things were about to get worse.

We wandered back to the base of the Salathé to do a route just left called Reed's Leads (10b). This route is a few feet left of a 5.11a Clint Cummins face route, but that looked too hard. Reed's Leads is a crack climb just to the left and I elected to climb this. This route follows a fun crack for most of a rope length and then does a dicey traverse right to the bolt anchors. I freed this route until I could reach the anchor slings and then just grabbed them. Seemed 10b to me. Homie followed, but didn't like the potential pendulum if he pulled my last piece. He tensioned over and we left the piece for Hardly to clean as he was leading up the pitch next.

When we got back on the ground (double rope rappel), I talked more with the group of three at the base of the Salathé. Their leader was still leading the first pitch - a three hour lead! I was extremely concerned and was asking if we could pass them. The tall guy said, "This guy won't be leading much more after this. We'll be faster. I've climbed El Cap 16 times and my partner other there has climbed it 85 times." "Damn!" I thought, "Who are these guys?" I turned to the tall figure and asked, "What's your name?" "Scott Crogrove," he answered. Doh! I was giving advice to this guy. I didn't just insert my foot in my mouth. I had it in up to my knee!

I had met Scott once before on Moses Tower and when I mentioned it to him, he remembered: "Oh, yes. Greg Epperson was taking photos of us on Pale Fire, right?" Scott is a nice guy who has climbed 5.14 and worked hard on freeing the Muir Wall a couple of years ago (getting it about 95% free). Today his partner was Steve Gerberding, who has not only climbed El Cap more times than anyone alive, but has many speed records on the monolith. Their "friend" (read: client) was named Robin. Later I would correspond with Robin via Email and read a trip report of his where he claimed other parties (including myself) jugged his lines and cheated him out of climbing the Free Blast start. This was erroneous and he knew that was case. So not only was he just jugging the whole damn route as a client, but he lied about it publicly as well. Cosgrove would be using Scott Burke's fixed lines to haul their gear and thought it would be okay for us also. That enabled us to climb Free Blast the next day without five ropes to fix.

By now the Loobster had shown up at the base and we were chatting amiably about what to climb next. Just then another team showed up to start Free Blast. Ack! We referred to this team as the "Fat Team" because these guys weren't skipping any meals. The woman in the group had breasts as big as Loobster's head. They were good climbers though - the leader would scooted up the 10c first pitch without any trouble. With this team there, we had to get in line. Hardly geared up to lead the first pitch as Scott and Steve headed up to fix the next two pitches. Before the day was out there were three sets of fixed lines on the Free Blast from the tops of the 3rd, 2nd, and 1st pitches. The zoo was on. I kept thinking "these things tend to work themselves out." Before leaving we'd find out that the Fat Team was heading up the Triple Direct (Free Blast to Muir Wall to the Nose) and wouldn't be a problem for us.

Hardly had no trouble with the first pitch and I followed without falling. I led the tricky, leaning second pitch. This pitch is rated 5.8 and probably would be if it went straight up, but the leaning nature of this crack and the incredibly slick rock makes me think it is more like 5.9. I led it clean, but had some trouble. Hardly followed and I lowered him back to the top of the first pitch, fixed the rope, and rappelled off.

While we were doing this, Homie, Judy, and the Loobster went off and did the challenging and awkward first pitch of Little John Right (5.8). When we wandered over to these three they were still fully engaged. Saying we'd see them back at the RV, we headed off to get organized for the next day.

When the Loobster and company arrived, we drove over to the turn-out on the other side of the valley. This is the first turn-out after you pass the Wawona (Highway 41) turn-off and the first time you get a good glimpse of El Capitan when heading east into the Valley. Here we parked the RV for the night. This flat location offers a perfect view of El Cap and we ended up spending three nights there without any problems from the rangers. This is encouraging news. The rangers apparently are taking the stance that there is no need to solve a problem until there actually is a problem. This is the same stance taken by the rangers in Grand Teton National Park. I've spent many nights camped in Lupine Meadows parking lot. If you don't make a fuss and don't show any signs that you're camping, no one will bother you. Just make sure you're up and packed away early in the morning.

After dinner we packed the haulbag in the dark. At one point I held up a sling with a #5 Camalot, a #7 Big Dude, and a #3 BigBro clipped on it and asked Homie, "What's this?" He looked at me quizzically and I answered my own question: "It's a Hollow Flake rack!" I was worried about this famous "turkey filter" pitch and trying to make light of it. This pitch is a 120-foot 5.9 offwidth, which is 7 to 9 inches wide. There is no way to aid it and unlikely to get much, if any, protection. This is the pitch that inspired Dr. Offwidth to learn how to climb offwidths. He saw God while climbing this pitch completely unprotected. The Hollow Flake is the mandatory free climbing crux of the route. Not to be confused with the actual free climbing crux of the route.

We were all up early the next morning. The Loobster, Homie, and Judy were off to climb the ever popular Nutcracker on Manure Pile Buttress while Hardly and I headed for Free Blast - the first 10 pitches of the Salathé. We didn't need a haulbag because we were using the standard strategy of hauling up the fixed lines to Heart Ledge to avoid hauling the lower angled slabs of the Free Blast.

We arrived at the base of the route a little past 6 a.m. and were glad to see that we were the first ones on the scene. I was jugging our fixed line by 6:30 a.m. Before Hardly left the ground two more climbers showed up - shod in matching white helmets. I assumed they were one of the other fixed rope teams, but when Hardly arrived at the belay I found out they were yet another team vying for the Salathé. I sighed in disgust. Dammit, didn't these people know we had reserved this wall.

As Hardly aided the 11b roof starting the third pitch, I watched the leader of the team below. He climbed confidently and quickly up the 10c first pitch and then combined the second pitch! I didn't think this could be done even with a 60-meter rope because the first pitch is a full 50 meters. The leader's name was Adam and he was from New Hampshire. He was out in Yosemite for a couple of months. His partner, Tom, was from Salt Lake City and had just come out to climb the Salathé. Adam seemed to have about the same level of experience that I had and Tom was similar to Hardly in that this was the first wall for both of them. The Salathé is quite an undertaking for a first wall. Most people start on Washington Column (1200 vertical feet) and then maybe Half Dome (2200') before tackling El Cap (3000+' for our route).

Eventually Hardly called down that he was off belay and the rope was fixed. I clamped on the Jumars and cleaned past the roof and up to the belay. Once above this roof, we couldn't see the base of the route any longer. I led the fourth pitch (10b) and, despite having flashed this pitch years ago, found it even greasier than before. I wasn't concerned about freeing the pitch but I certainly wouldn't allow myself aiders. I grabbed the occasional piece as I worked my way up. I worked up quite a sweat and at one point I looked down and saw the party behind us reach Hardly's belay. These guys were fast! But something was wrong. The guy down at Hardly's belay wasn't wearing a white helmet. What was going on? No way another party could have arrived at the base, geared up, and climbed three pitches in the time I led half of one pitch. Maybe the guy had removed his helmet for some reason. I turned my attention back to the climbing and was soon at the belay. Once I called down "Off belay," Hardly responded with, "Bill, we're going to let these guys pass because they are going really fast." "Okay!" I said and sat back to watch the show.

I was disappointed that these guys were passing us and taking our position on the wall, but I couldn't hold back a team moving that much faster than us. I watched in silent admiration as the leader almost ran up the pitch below me. He was placing gear 30-40 feet apart. From his last piece to the belay, I had placed six more pieces! By the time he arrived at the belay I knew he wasn't Adam or Tom. This was indeed another party. An amazingly fast party! The leader clipped a quickdraw to my belay and moved on up the 5.10d shallow crack above. What most struck me as he moved by was not the ancient, floppy climbing shoes he wore, but the size of his rack. He had only one #3 Camalot and just a handful of other gear. And he was leading two pitches at a time! This guy was Superman!

He moved as if the slab was 5.6 and I started to think that maybe it was. Maybe the 5.10 climbing was up on the bolt-protected face above. Once again, he had more than 30 feet between placements. High up on the slab, he fell off. And slid down the slab past his last placement, but then he kept on falling. I looked down to see his belayer still feeding out rope through his Gri-Gri. I relayed the "Falling" command down to the belayer and finally he caught the falling leader. It was about a 45-foot sliding fall. Disgusted with falling, the leader clipped into an intermediate belay and called off belay. He had too much rope drag - one of the drawbacks of leading with a 70-meter rope. He brought his belayer up to my belay and then asked me if it was okay to lower back down my belay so that he could lead it again without falling. I felt some pressure from the teams behind us, but I also knew I was watching something special. I agreed and he quickly lowered back down.

The leader's name was Jim Herson and he looked remarkably like Olympic gold medalist Frank Shorter. Jim was attempting to redpoint the entire Salathé. He had been working the route and now wanted to lead every pitch free over the next 1.5 days. His belayer was 6'5" Peter Coward. Peter was no slouch himself. He was following every pitch while wearing a sizeable pack. There plan was to climb up through the 24th pitch (the notorious Teflon Corner) today and than descend to bivy on the Spire that night. They'd then finish the route the next day. I got all this information from Peter while Jim was re-leading the 5th pitch.

Peter was hoping to be fresh enough to get the "11c" crack pitch above the Spire clean (he didn't get it this time). He remarked that this pitch was a sandbag and was more like 5.12a. Scott Burke would, later, independently say the same thing. I'd find out later that Peter owned many El Cap speed records. These guys are the superstars of the Valley. Jim finished off the pitch, Peter took off, and they both faded into the distance, but not from mind. I was jealous of their ability to turn a 5-day aid climb into a long free climb. They climbed relatively unencumbered while we lumbered along with a monstrous rack, aid gear, and a haulbag. We weren't just at different levels. These guys were practicing an entirely different sport.

Hardly started leading the "5.6 slab" and almost immediately was on aid. Apparently it really was 5.10d. Jim had deceived us with his ease. Hardly did a good job leading this pitch in that he backcleaned all the bolts that go off to the left and then back right. This made it trivial for me to clean. Hardly had to do some free moves between the widely spaced (for aid climbing) bolts. I led the 6th pitch with some aid up to a good ledge and relaxed while Hardly freed the 5.9 pitch up to the hanging belay beneath the Half Dollar.

The Half Dollar is a huge, round feature stuck onto the slab. It forms a large roof underneath and a steep right facing dihedral on its left side. This pitch is rated 10b or 10c depending upon which year of the guidebook you look at. Pitch ratings on El Capitan can vary widely. For example, the pitch below the Salathé Roof was rated 5.11d in the first two editions of Meyers' guide (1982, 1987); then 5.12b in Meyer's Yosemite Select guide (1991); then 5.12d when Alex Huber freed it, but the rating is back down to 5.12b in the topo published by Chris McNamara in Rock & Ice (1999, issue #91). The pitch below this, the one just off of Sous le Toit ledge has been rated anywhere from 5.10c to 5.11d. It's current rating is a very solid 5.11b.

Whatever the rating, the Half Dollar pitch is damn hard. I didn't free the section around the corner. The pin scars would either take fingers or Aliens. I plugged in the Aliens and did a couple of aid moves to get by this section. The next section of this pitch is classic Yosemite: a steep, intimidating flare rated 5.8, but feels much harder. I ran out the rope to a bolted belay on a good ledge. It is nice to lead the even pitches when doing the Salathé since the belays are much nicer than the odd pitches.

Hardly followed and we quickly polished off the last two moderate pitches to the top of Mammoth Terraces where we arrived at 2 p.m. From here the Salathé route rappels down to Heart Ledges. Luckily there was a fixed rope here also and we coiled our ropes and started the descent. While descending we ran into the third member of the Triple Direct team that had fixed a line on the Free Blast yesterday. He was hauling the gear while the other two were climbing Free Blast.

I stopped at the top of the last rappel and Hardly stopped at the top of the second to last rappel. Down on the ground was our loyal support crew of Loobster, John, and Judy. They had carried the haulbag (90 pounds? It had 52 pounds of water in it) over to the base of the fixed lines. These three had an enjoyable climb up the five pitch 5.8 Nutcracker with everyone getting to lead some. Loobster led everything 5.8 and harder so that John and Judy could get used to Yosemite climbing without the stress of leading.

Loobster jugged up the fixed line to me and we dropped the haulline to the base where Johnny attached it to the bag. Now for the tricky part: lifting it off the ground. I threaded the line through our Wall Hauler and clipped onto the other side with my jumars. I was going to try a technique called body-hauling for the first time. As a safety precaution, I had Loobster put me on belay with an extra rope. Now, with my entire body weight (probably over 180 pounds with gear) as a counterweight, I was easily able to move the bag up the wall. As I went down, the bag went up. I was amazed how easily this worked. Of course, once down at the bottom I needed to jug back up to the top, but that was immeasurably easier than conventional hauling.

We clipped the bag into the rope Hardly was dangling from the next rappel point and he started hauling. I jugged a fixed line until I could switch over to the dangling haulline and we repeated the body haul technique. Using this and a combination of conventional hauling, we quickly got the bag to the top of Heart Ledges where we ran into Adam and Tom who were just starting their descent. Their plan was to follow us up the next morning, but I was worried that they'd change their mind and haul their gear all the way to Heart Ledges also and then sleep up there. Then they'd be ahead of us the next day and put us a day further behind. Our plan was to descend and spend one more night in the RV with our friends before cutting our ties with the ground. The reason for this was the bivy situation. Cosgrove's party had given up on climbing Free Blast because of the zoo. They instead headed up the fixed lines and were going to bivy on Lung Ledge, one pitch above Heart Ledge. Since they were spending the next night on El Cap Spire, there wasn't much point to us spending the night up here since we'd have to sleep on Hollow Flake Ledge - just three pitches away - the next night.

We rapped back to the ground and hiked back to the RV, which we drove over to our familiar parking area for the night. We relaxed, ate a hot dinner, and went to bed early. The Loobster trio was off to climb Royal Arches the next day and wanted to be off very early. We didn't need to get going early because of the amount of climbing we had to do was so little, but we didn't want to lose our position on the wall either.

The next morning we said our good-byes to Loobster, John, and Judy. Blasting off from the ground and leaving the security and companionship of our friends was a bit scary and lonely. I wondered if this was truly what I wanted to do. Even if it wasn't, I wouldn't be turning back. I couldn't do that to Hardly. I'm not sure I'm really made for climbing walls. Leaving the ground is always the hardest part for me. Once up there, I'm fine. I'm usually not too frightened and enjoy the climbing. And I'm focused on doing the work to get me to the top. I don't think about retreat. But it's the transition from the safe ground to the wall - to the isolation and commitment - that wrenches my gut.

We quickly jugged to Heart Ledge and changed into free climbing shoes. Hardly led a 30 foot pitch up to the upper ledge where we found a party of three bivouacing. They were still asleep when we arrived, but that didn't last long as I had to climb right over them to start the next pitch. They were wall veterans and more concerned about toking up, then climbing. They were headed to the Shield so our routes diverged here as they headed up the fixed lines to Mammoth Terraces. To get to the Shield the climbers than follow the lower part of the Muir Wall - yet another traffic jam section.

I did some dicey friction moves right off the ledge. I climbed left and up before I could get any gear. I worked further left under a roof - French Freeing the lower section. The crux move is right by a bolt and is rated 5.11c. It looked very hard and I quickly just stepped in my aider. I used a combination of aid and free moves to quickly climb the upper 10b section to a bolt on the edge of Lung Ledge. I fixed the line here and hauled the bag. The hauling wasn't too bad as long as you could put your entire body weight into the haul. It was essential to have a steep wall to do this. I tied in with twenty feet of slack so that I could haul the bag in longer bursts.

Hardly led the 4th class pitch to the upper end of Lung Ledge and I followed while pushing the haulbag over the numerous ledges. We dislodged a sizeable rock here and I yelled "Rock!" We were way left of anyone on the fixed lines, but there are routes all over this stone. At the belay, I switched out of my hard-shelled kneepads and into my neoprene free-climbing kneepads. This was a trick taught to me by Dr. Offwidth. These kneepads weren't as thick, but they absolutely will not slide down your leg. They are so tight that they must be worn under my pants. I grabbed my tiny rack of a #3 Big Bro, a #5 Camalot, a #7 Yates Big Dude, and a few slings. It was time to rock. Bring on the Hollow Flake!

I had long aspired to climb the Salathé Wall and in my many years of preparation I sought out offwidths and chimneys so that I'd be ready when the time came to lead this horror show. I had honed my skills on most of the nasty 5.9 wide cracks in the Valley, including the rarely done third pitch of Reed's Direct. But with all my practice, 5.9 seemed to be my upper limit for flashing offwidths. I'd have to flash Hollow Flake or take a 100+ foot fall. I was apprehensive.

Climbing up to the pendulum point was tougher than expected and I carried no gear to place on this section. Thirty feet up I clipped into the pendulum point and discovered an abandoned rope here. We'd use this rope to lower out the haulbag and for Hardly to lower himself out before jugging up. This rope proved handy and helped us avoid the only problematical section of the route if you are climbing without a tag/lower-out line.

I had Hardly lower me down. I made one try at traversing over, but was still way too high. Of course trying to go across as high as possible is just human nature. I wanted to avoid as much of the offwidth as possible. Unfortunately, I needed to lower way down before I was able to pendulum into the crack. Once established, I was very intimidated by the prospects ahead. It was a long, long way to the belay and the only avenue was up a big, nasty crack. I started up.

I put my right side into the offwidth and made steady progress up to the crux section where things closed down to about 7 inches. Many people lieback this section because it is much easier to climb that way. I was too afraid to try this technique because of the danger of exploding off the wall. At least with offwidth technique there is a chance of sliding back down the crack. Here I was able to place the #7 Big Dude and I could slide it up the crack a bit. I put two long slings on it and left it behind as I struggled desperately through the crux. The climbing here was very hard and I barely made it through without falling. Unfortunately, once above this section is was painfully obvious that I wouldn't be able to continue because of the rope drag. The big cam below was still below my pendulum point and the Z-pattern was just too much drag. I would have to descend to remove it.

I placed my #3 BigBro and clipped it. Of course the drag is even worse now and I could barely go downwards. I stretched as far as I could and managed to unclip the double sling from the unit. I just let the slings drop - hoping that the piece wouldn't fall out of the crack as it had now turned around to point upwards. The piece didn't drop and Hardly would retrieve it while cleaning. Now the climbing eased somewhat - probably to about 5.8, but it was completely unprotected and was still an offwidth. The belay was sixty feet above me and I knew I'd have to run it out. I resisted the urge to just go as fast as I could in an effort to get it over with. I'm was afraid if I did that, I would burn out and become more desperate. I needed to be solid here. I struggled up ten feet at a time and rested. I could get a pretty good rest in the crack because it leaned back a bit and I would let my breathing recover a bit. As I got closer and closer to the belay, I felt myself wanting to go faster so that it would be over. I resisted and remained solid to the top. It was done.

Hardly followed this pitch with aplomb. He had already followed his first pendulum on the 6th pitch of Free Blast, so he was experienced. He used the abandoned line to lower himself out, but it wasn't long enough. He'd be going for a bit of a swing, but seemed unperturbed by this prospect and let go. He jumped over the flake on the way by and soon was jugging up the crack.

We surveyed our bivy spot on Hollow Flake Ledge. This was the last ledge before the Spire and hence we needed to stop here. Actually, there is a bivy spot one pitch down from the Spire called the Alcove, but we wanted to sleep on the Spire. It was a classic bivy location. Every climber has seen the famous photo of Royal Robbins reclining on this perch. Our current accommodations were secure, but cramped. We'd sleep foot to head wedged together between the main wall and a rock outcropping that formed a small box to lie in. It was only 2:00 p.m. Time for lunch and relaxation.

After a long break, Hardly borrowed my kneepads and started up the unprotected and intimidating 5.7 (most think it is more like 5.9) chimney which formed the next pitch. This chimney leaned a bit so it wasn't that steep, but it was also flaring so that Hardly needed to bury himself deep in the crack to feel secure. He was able to place a couple of pieces on this pitch and steadily worked himself up to the belay. He fixed the line and returned to our ledge. We read books and napped until dinner time. Just before dinner I whipped out my cell phone and called my wife Sheri in Colorado! How things have changed...

Hollow Flake ledge and "5.7" chimney above it.

Hollow Flake ledge and "5.7" chimney above it.

While eating dinner, we heard someone grunting up the Hollow Flake. Eventually Tom pulled onto our ledge huffing and puffing. He looked like I felt when I finished that pitch. He was so out of breath that it was awhile before he could speak. He couldn't do the offwidth moves at the crux and resorted to desperate liebacking. Tom was just fixing this pitch so that it wouldn't be hanging over him all night long. He descended back to Lung Ledge for the night.

We had a delicious dinner of Spaghetti O's, Fruit Cocktail, and vanilla pudding. The next morning we were moving early, though we didn't have than many pitches to go. It was six pitches to our bivy location, but we knew we'd have to fix a pitch above the Spire to have any chance of making Long Ledge the next day. Hardly jugged the fixed line and hauled the bag. I followed while trying to keep the bag out of the chimney.

The next pitch is rated 5.10a and I freed all of this pitch except for one tricky section - presumably the 10a section. Hardly freed the next 10c pitch (10d in the 1991 Select guidebook). This certainly saved us a lot of time. Now it was time for me to deal with the second infamous wide pitch on the Salathé: the Ear.

The 10a pitch.

The 10a pitch.

Looking up at the Ear.

Looking up at the Ear.

The Ear pitch starts with some 5.10+ climbing around a roof and I aided this part to the base of the chimney. The Ear appeared much more intimidating than I had anticipated. Above me was a great gaping maw which pinched down to nothing at the top. I had to climb up into this Bombay chimney and then work my way out to the right horizontally to escape the chimney before it got too tight to move upwards. I wormed my way up into the slot and placed a giant cam well over my head. Facing out toward the valley, I moved now to my left. The climbing was hard but I could see some face holds further away and slowly inched toward them. The chimney is so tight for my head and upper body that I had to move downwards if I wanted to turn my head. I should have removed my helmet before leading this pitch for it severely restricted my head movement. On the other hand, my lower body was in a wider flare and struggled for solid purchase.

Exiting the chimney is easier than it looks and I was now faced with a wide crack that led up to the belay. A #4.5 Camalot fit into this slot and I was soon at the belay on a tiny stance on top of the Ear. I was able to flip the haul line outside of the Ear and the hauling went easily since the bag hung completely free of the wall. Hardly had an interesting time cleaning the traversing chimney, but by now he was used to swinging around on jugs.

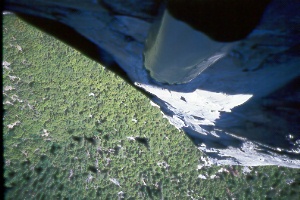

Looking down from the Ear

Looking down from the Ear

Surprisingly, and everything is relative on El Cap, the Salathé isn't that steep for the first 17 pitches. Things head sharply toward vertical with the Ear pitch, but the exposure doesn't get that great until turning the Salathé Roof. The reason for this is the abundant ledges and stances on this route. This is in sharp contrast to the Nose where there isn't even a stance from Sickle Ledge (top of pitch 5) to Dolt Tower (top of pitch 12).

The next pitch was a 150-foot monster. This is the infamous 5.13c pitch which most free climbers have avoided. The alternative is a sparsely protected 5.12b/c undercling which leads left and downwards over to the 5.11a offwidth of Bermuda Dunes. Alex Huber fell out of this offwidth on his first attempt, so it isn't a picnic. The offwidth is also very run-out unless the leader has many large cams. Hardly started up the crack and immediately was having trouble with the awkward flaring nature of the crack. This lower section is supposedly 5.10d fists, but it is so continuous that is appears much harder. Above there is a roof and then a thin crack forms the free climbing crux while the aid difficulties ease. Hardly spent 2.5 hours leading this pitch. I'm not sure why it took this long. Certainly lots of backcleaning was required and at one point he hauled up the large cams. Maybe he was just freaked for some reason. Probably just a difficult pitch to lead and he is relatively inexperienced leading aid. Nevertheless, it was frustrating standing on this tiny stance and shivering.

.jpg) Pitch

19: 10d fists to 5.13c tips.

Pitch

19: 10d fists to 5.13c tips.

Despite climbing El Cap in early June, the weather was treating us well. It wasn't that hot up on the Salathé since this section of El Cap doesn't receive any sun until the afternoon. We climbed most of time in our pile sweaters - at least on the upper half of the wall. I almost always belayed wearing my pile. This is perfect conditions and we would top out with plenty of water left.

After an eternity, the "Off Belay! Rope's fixed! Ready to haul!" command reached my ears and I was set free of the tiny perch. At Hardly's belay, I was faced with yet another wide pitch. A 10a offwidth led to the Alcove bivy. The difference with this wide pitch is that it was easily negotiated with a couple of judicious pulls on a #5 Camalot. Soon as I at the lower bivy, but our goal was the Spire and I knew the next pitch could be combined. Now most topos show the pitch up to the Spire to be a 5.6 chimney, but the latest Chris Mac topo show this as a 5.10a hand crack. Actually it is both. The latter has gear as often as you need it. The former looked positively terrifying. It shouldn't have bothered me so much. I had done the Hollow Flake. I had led the unprotected Texas Flake pitch on the Nose. This was supposedly only 5.6, but it looked tricky because one wall of the chimney was actually the arete on the Spire. It seemed all too easy to slip off this arete. Bottom line: I wimped out. I didn't even fire the 10a pitch, which I thought was harder (I know, I sound like a broken record). In fact, I pretty much just aided the pitch. This went straightforward until I had to get on top of the Spire itself. The crack slants further and further away from the Spire, making it a big reach and a desperate mantle get on top.

Chimney to the top of the Spire and on the Spire

Chimney to the top of the Spire and on the Spire

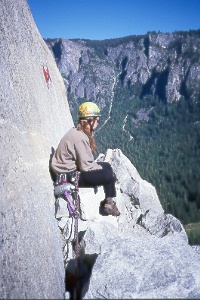

I was really getting used to arriving at bivy site early in the day. We were setting no speed records, but I really enjoyed this pace. We had great bivy ledges in the most incredible, exposed positions. Once again, we took a break and relaxed before Hardly started up the sandbag 11c pitch off the Spire. Hardly aided this pitch and was much quicker than he had been on his last lead. He was getting a rhythm. The end of this pitch is a mandatory 5.9 squeeze which Hardly ran out confidently.

While Hardly was working away, I talking with Chris McNamara who was climbing the immediately adjacent Excalibur. Chris was climbing with Craig Luebben, one of the best offwidth climbers in the world. Craig wanted to try and free the three 5.12 offwidths on this route. Steve Schneider is the only person to free these brutal fissures. Craig failed on his attempt. Apparently they required some bold liebacking which Craig was not prepared to do. This is surprising that the cracks wouldn't succumb to stacking techniques.

Chris is only twenty years old but has climbed El Cap 50 times. This was his first trip up Excalibur. Chris also mentioned that he hasn't climbed Mt. Watkins yet but plans to this fall. I can't wait for the beta as this route is high on my list. Apparently Brooke Sandahl and partner had recently free climbed this route. I knew that Peter Croft and Dave Shultz tried to free climb it, but fell short.

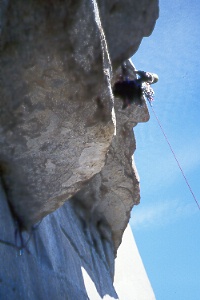

Hardly leading the "11c" pitch, which is really 5.12a.

Hardly leading the "11c" pitch, which is really 5.12a.

Hardly finished his lead, but instead of him cleaning it on rappel, I started up. Since we only had two ropes, we could only fix one rope (we needed the other line to haul the bag) - but this didn't mean we could only fix one pitch. I cleaned the pitch and decided to lead until I ran out of rope. I aided up the beautiful 11a corner and got with a move or two of the top before I ran out of rope. I anchored the rope to four bomber pieces (why not? I didn't need them for anything else) and rappelled back down to Hardly. We anchored the rope at the top of this pitch also and rappelled back down to the Spire for dinner. Yum! Spaghetti O's again. We both decided that next time we'd bring more food and less water. Heck, we could have brought four more cans of food in the same space and weight as one 2 liter water bottle.

Once again, Tom arrived at our bivy site in the evening. We had spread ourselves all over the Spire and didn't want the extra company. Tom obliged us and rappelled back down to the Alcove bivy. After reading a bit, we slept.

While we were working our way towards the Spire bivy, our friends were climbing Half Dome. Loobster led all the pitches on the moderate classic Snake Dike, while John and Judy were content to follow. There are 100+ foot run-outs on this climb. Hence, the leader needs to be very solid and very confident. They had no trouble with the route and cruised the roundtrip in about 12 casual hours. That evening the Loobster headed back to Santa Clara for a couple days of work. John and Judy would get a couple of semi-rest days, which were well deserved after the string of days with the Loobster.

The next morning the alarm went off at 5 a.m. We knew we had a long day ahead of us. As I'm lying there in my bivy bag gazing up at the gloom of the upper headwall, I spot a dark shape swooping down the wall. Immediately, I called out "BASE jumper!" and point so Hardly can get a fix. This guy was a pro. He maintained perfect body position: head down and slightly in front of the rest of his body; arms swept back behind him. He rocketed toward the earth and pulled his chute around our height. I watched him make tight circles down towards El Cap Meadow with this high performance square chute. He landed so close to the trees on the west end - confirming again his expert status. I turned away, thinking that the show was over, and went about the business of packing up.

Later I would find out the jumper, whose name was Frank Gambalie, was indeed an expert. But the rangers had been tipped off about this jump and were waiting for him in the Meadow. A chase ensued. Frank won the race to the Merced River, turned, gave the rangers a big smile, and jumped into the swift current. Obviously his plan was to float downstream faster than the rangers could pursue, get out downstream, and make his way out of the Valley. Unfortunately, he had underestimated the power of the river this early in the year. His body was never found. His friends confirm that he has indeed been lost. The rangers searched the banks and called in helicopter support to no avail. This is a copy of the news wire report on the incident:

99-267 - Yosemite NP (CA) - BASE Jump; Search

At first light on June

9th, a man jumped from El Capitan and parachuted to the floor of Yosemite

Valley, landing in El Capitan Meadow. Rangers John Stobinski and Tom Schwartz

saw the jump. As the jumper was disconnecting his harness, they identified

themselves and ordered him to stop. He looked at the rangers, smiled and fled.

The rangers gave chase for approximately 500 yards until the jumper entered the

Merced River, swollen by spring run-off. He was swept downstream and was not

seen again by the rangers. A search of a two-mile stretch of the Class 3 Merced

River was conducted utilizing the park's contract helicopter and ten

swiftwater-trained rescuers. The jumper was not located, and it's not certain if

he got out of the river. Evidence indicates that he was an experienced and

professional BASE jumper named Frank Gambalie. Gambalie is reported by close

friends as reliable and punctual; he was expected home in Lake Tahoe on the

evening of June 9th and had a job appointment the following morning. He didn't

make either of these appointments, and, as far as investigators have been able

to determine, has not called any friends or relatives. The search continued on

June 10th. Gambalie's vehicle was found parked near a trailhead that leads to

the top of El Capitan. No further sign of him has yet been found. [Scott Hinson,

YOSE, 6/12]

A tragic loss. I don't think anyone was really at fault. I think BASE jumping should be legal in Yosemite, but given that it is not, the rangers aren't at fault for doing their job. Guy just made a mistake with the river. This is easy to do. Rivers frequently don't appear as the death traps they really are. Water is a very powerful force. Like gravity! Back to the climbing.

We ascended our fixed lines and it took me hardly any time to finish off my pitch. After a couple of aid moves the climbing eased to 5.5 and I had to run-out the rest of the pitch to avoid running the rope left, up, then back right. This made it easy and fast to clean. At the belay I found a fixed line on the next pitch, the Teflon Corner. I wanted Hardly to jug it. I thought it would give us some insurance about making Long Ledge that day. But he'd have none of that. "I came to climb this wall, not jug it," he said. I bowed my head in shame at this comment. "Yes," I thought, "I came to climb it also." Later he would say to me, "You wouldn't have jugged it if it were your lead." I'm not so sure.

Hardly led this steep pitch in a little over an hour - not bad. Next up was the worst pitch of the route. The so-called "Jungle Pitch" is named for its propensity to be wet. It didn't disappoint. This was some of the trickiest aid I had to do on the route. Dry, the pitch goes free at 10c and I mixed in free moves with aid climbing as I fought my way up this slimy mess. To top it off, the pitch ends in a complete hanging belay below a roof from two ancient quarter-inch bolts. I momentarily thought about combining the next pitch, but wasn't sure it would reach. I was also well aware that Hardly was quite happy with how the pitches were going to work out and he didn't want that order messed with. In other words, he wanted to lead the Salathé roof.

Bill in

the "Jungle".

Bill in

the "Jungle".  Hardly on the Block pitch.

Hardly on the Block pitch.

I backed up the crappy bolts with a couple of cams under the roof and hauled the bag. The change-over at this belay was slow and awkward. Finally, Hardly was off - hand jamming the 10a corner above the roof. He made quick progress until the corner got much steeper and the crack thinner and more flared. He dropped back into aid mode and made steady progress to the Block. Hardly climbed to the ledge above the Block and shortened the next pitch by about thirty feet. We took a short break here to eat and drink. We still had a long way to go: three pitches to the roof, then three more pitches to Long Ledge - the next bivy opportunity once leaving the Block. We wondered what Adam and Tom would do behind us. The logical decision was to bivy at the Block. They probably wouldn't make Long Ledge before darkness and it was only supposed to be big enough for three people.

The next pitch leads to the fabulous Sous Le Toit ledge. This is apparently where many parties get off route. I didn't have any trouble figuring out where to go and enjoyed this pitch. I climbed up some moderate flakes to an crack where a couple tricky placements of aid led me up and left to the pendulum point. Yes, Hardly got to follow yet another pendulum. This led to a beautiful 10c lieback crack which I aided, of course! The pitch ends on a small, but perfect ledge. Two new bolts high on the wall and off to the side make for easy hauling and the perch forms a great seat and allows for a partial unpacking of the haulbag. The position is extraordinary: 2500 feet off the ground, 180 feet below the looming Salathé Roof. From here we got our first good view of the roof. It looked intimidating as it loomed over us.

Leading to Sous Le Toit.

Leading to Sous Le Toit.  Pitch 28: 5.11b/C1

Pitch 28: 5.11b/C1

The next two pitches can be combined into one pitch with a 60-meter rope. Done like this the free rating is 5.12d according to Jim Herson. We did separate pitches. Hardly led the first one which is about 100 feet long and rated 5.11b (5.10c in the 1991 guide). Hardly freed the lower 5.7 section, but aided most of this pitch. It ends at a pure hanging belay from new bolts.

The Sous Le Toit ledge was my favorite belay of the climb. Here I talked more with Chris McNamara as he is pounded his way up Excalibur. Starting to get cocky about having this route almost done, I queried Chris for what route to do next. "What's the next easiest route on El Cap after the Nose and the Salathé?" His response was immediate: "Lurking Fear is easier than both of those routes." Cool. I then asked him the best way to follow the big roof since I didn't want to follow on jumars. "On aiders, with a Gri-Gri as a self-belay," he responded. "What if I don't have a Gri-Gri?" I asked the young master. "Tie in often!" Yikes! This would be a new experience...

I led the next pitch (rated 5.12b or C2+) and found the going easy to begin with. Halfway up the pitch I got a better look at the upper part of the crack and was horrified that it wasn't really a crack at all. It was more like a little wave of rock that curved over to form a small flare. I said out loud, "How the hell do you climb that?!" It looked impossible to get anything to stick here and I now realized why it gets a C2+ rating. Discouraged, I moved upwards without a good plan. Apparently this section was originally climbed with bongs. Higher up I was equally surprised to find that medium to large cams worked! The pieces don't look like they could even support their own weight, let alone my weight. This technique worked well and I cautiously made my way up to the hanging belay directly under the roof. I was dismayed to find only old bolts here. I know Skinner and Piana had set-up their porta-ledges at this sheltered location while they worked on freeing the headwall and had assumed they placed new bolts. Not so. The belay here is from three old bolts and a bong. It's sufficient, but I had been on a steady diet of shiny new bolts for the last couple of pitches.

Though I had a butt bag along with me, I was too lazy to get it out. I found it equally as comfortable to just sit on top of the haulbag like it was a horse. Hardly cleaned quickly and set out leading the huge roof. This pitch first traverses right before climbing up to the lip of the roof and traversing back left a bit before turning the roof. This pitch is almost completely fixed. Hardly only had to make about six placements to complete the lead, yet it still took a long time to lead this 75 foot pitch. Hardly had lots of trouble getting over the roof. I think one of the trickiest placementss are right over the lip. Adjustable daisies probably would have helped a lot.

Starting

and turning the Salathé Roof.

Starting

and turning the Salathé Roof.

While belaying Hardly on the roof pitch, I watched Adam and Tom appear on Sous Le Toit below. They could fix from there down to the Block and bivy. I hoped they'd do this instead of crowding us at Long Ledge. The Long Ledge bivy didn't have an alternative. It was either bivy at the Block or Long Ledge. The smart thing for them to do, I thought, was to bivy at the Block. They'd never make Long Ledge before dark anyway. Also, we all knew that Long Ledge was a bivy for two or three. Though they supposedly knew of an incident where six people spent the night there. I didn't want to spend the night sitting up because these dicks climbed up to our bivy. Unfortunately, before I left the belay under the roof, I knew they were going for Long Ledge. They were leading up towards me.

When the call came down, I took Hardly off belay and cut the haulbag loose. It took a wild swing out away from the wall and then swung back in straight toward me! I avoided being pummeled into the wall and got myself organized for my first try at self-belay aiding. Doing this 2700 feet off the ground seemed like a good place to practice. I tied in at regular intervals just as my coach suggested. At the lip of the roof, I switched over from aiding to jugging. As I turned the roof, I saw Hardly about thirty feet above at the belay - standing on top of the haulbag! He said, " Bosson's Chair? Bosson's Chair!? We don't need no stinkin' Bosson's Chair! We have our own portable ledge!" It looked hilarious, but was very comfortable for him.

The awesome Salathé Headwall!

The awesome Salathé Headwall!

Time was getting to be an issue for us. It was 7 p.m. and we still had the entire headwall to climb - two pitches which led directly upwards at an angle slightly past vertical. The first pitch, mine, was ultra-classic and 130 feet long. The initial thirty feet or more of this pitch seemed like it would go free at 5.10+/5.11. There are some decent hand jams and fingerlocks on this section. I didn't free it of course, but the jams allowed me to top step on the Salathé headwall! I cruised the first 50 or 60 feet and was backcleaning like mad. I just left the red and yellow Aliens on my aiders and just kept shuffling them up. As my rack got smaller, I got slower. I worried that I'd run out of gear and worked hard to not leave my trusty Aliens behind. This pitch passes over a couple of tiny roofs and ends at a bolted, hanging belay.

Paul Piana, in his book "Big Walls", calls the Salathé headwall "the grandest climb in the universe" and thought climbing (either free or aid) on it is "one of the most overwhelmingly good experiences a rock climber can have." Todd Skinner, the first person to free the first two headwall pitches (Skinner and Piana broke the headwall into three pitches), called the crack splitting the headwall "the most beautiful crack I've ever seen." Indeed, this crack is gorgeous and the initial climbable section had me dreaming of freeing this pitch. But it will forever be a dream.

Cleaning, Hardly had a tough time on one piece and just before I yelled down to leave the piece, he got it out. The last pitch of the day is only fifty feet long, but it has an awkward wide section that stymied Hardly for a long time. There was lots of movement going on up there, but no rope was being pulled out. He step up and then back down. Up and down. Apparently he couldn't get his fifi hooked. Ajustable diasies would have made short work of this problem. The climbing looked hard., though. Above that was C2+ aid on tiny RP's. In fact, Hardly took a small fall when one of the RP's popped on him. This was our only fall on the route, I think. A black Alien just below the RP caught his fall and he went back up to put in the RP. Then he had to crank free moves directly right to reach Long Ledge.

Getting dark as Hardly leads the second Headwall pitch to Long

Ledge

Getting dark as Hardly leads the second Headwall pitch to Long

Ledge

I froze at the belay. Squeezing the metal Jumars as I cleaned the pitch, drained the last bit of heat from my hands. The cleaning went easily until Hardly's last piece - a black Alien. The rope went through this piece and then sideways for twenty feet. The climbing was still too hard to unweight my jumars and I wondered how I'd clean the piece. In fact, I got a bit irate. "How the hell do you expect me to clean this goddamn piece?!" I yelled. I immediately regretted my childish outburst. I was cold, frustrated, and desperate to make the ledge before it became pitch dark. Hardly knew all this and calmly let my tirade subside. This brings up a good point about wall partners. You better get along absolutely great with your partner, but because on a wall this relationship can be tested to the limits by the stress of multi-day big wall climbing. I think this was our only incident of stress between us and it lasted about two minutes. It probably isn't a coincidence that both our first fall and our first cross words occurred while racing for the bivy at the end of a long day.

I was able to jump one jumar over the black Alien and then lower myself out with the other jumar. I didn't think this would be possible since to weight the upper jumar should have jammed the lower jumar against the piece, but I guess I could get enough weight on my feet by smearing to make it possible. I lowered myself sideways for about fifteen feet so that the rope ran through my top jumar, then fifteen feet left to the piece, then back fifteen feet right to my lower jumar. Once I got to the point where I could completely un-weight the lower jumar, I jumped it around the piece also. Then I free climbed up and back left on bigger holds to a shiny bolt above the thin crack. I don't know if the bolt was placed to avoid this exact scenario or if it was just the first piece on the 5.12 free variation off of Long Ledge. In his haste and the dim light, Hardly had not seen this bolt. I clipped the rope into this bolt and down jumared to clean the black Alien.

By the time I arrived at Long Ledge my hands were completely numb. In June! The defrost time on Long Ledge would make me irritable as I moaned in pain. We hurried to get organized: unpacking the haul bag, clipping everything in, getting the headlamps on, the pads out, the sleeping bags, dinner, etc. We occupied the far east (right) end of the ledge because we knew Adam and Tom would be joining us eventually.

Each night on the wall we split a can of fruit. This was definitely a treat and one I will be repeating. The sweet liquid filled me up, energized me, and quenched my thirst all at once. I tried to use the cell phone to call Sheri even though it was really late, but it didn't work. I got the flattest bivy spot, but it was extremely exposed. Hardly spot was lumpier but had a ridge preventing him from dropping over the edge. My spot was pretty flat and quite comfy, but it was only about two feet wide with a vertical wall above me and an 2700' overhanging wall below me. A roll of a few inches would have sent me over the edge until my tether would stop the fall. Despite this I wasn't worried at all. I was too tired and slept reasonably well.

Adam arrived at Long Ledge at 1:30 a.m. and besides yelling "Off belay" down to his partner Tom, was remarkably quiet. In fact, I don't even recall Tom getting to the ledge or them unpacking the haul bag and settling in for the night. Either I was incredibly tired, they were incredibly quiet, or both. The next morning Adam recounted the epic they had the night before. Halfway up the headwall pitch Adam's headlamp batteries died. In pitch dark he had to somehow haul up a spare set and change the batteries. He had visions of spending the night standing in slings in the middle of the headwall. He put both headwall pitches together to save time and continued, very slowly, to the ledge.

The next morning we took at least an hour to straighten things up. We had things clipped all over the place. Adam and Tom were in no rush to get going so we took our time. The free variation to the Salathé climbs up a 5.12a bolted face on the far left end. Skinner first bolted and freed this pitch and it is supposedly stellar. But too much for me. I took the traditional aid pitch on the far right side of the ledge.

Getting started on this pitch is a bit unnerving since the RP sized crack starts a tiny bit right of where the ledge ends. I stood precariously at the end of the ledge - already 15 horizontal feet from the anchor - and struggled to get some gear. I placed two bomber RP's and black Alien before leaving the ledge and felt very secure. This pitch is rated C1+, but it isn't that challenging if you have experience with RPs. I was to find out later that Steve Gerberding (guiding the slanderous Robin) had taken a fall at the start of this pitch. Climbing in Boulder's Eldorado Springs Canyon, I am very well versed in the art of RP placements. The really challenging part of this pitch is the "5.8" free climbing. No way! This pitch does have some free moves on it and does finish up with 5.8, but the upper part of this crack is tricky. Just before the crack disappears for good, it veers to the left and becomes thin and parallel sided. My last piece of pro was at my feet and I felt the moves here were at least 5.10. I didn't want to risk falling. I thought either I was hosed or forced to make run-out 5.10 face moves, but I eventually got in a Lowe Ball into the crack. This was the only time on the entire route that we placed a Lowe Ball, but it was well worth carrying it for this single placement. Without it, the climb would have been very much in doubt for me. I tenuously weighted this dubious piece. It held and I top-stepped and, leaving my aider behind, committed to freeing the rest of the pitch. Once again, I later found out that a piece was missing here. Steve Gerberding had called for a rock, hauled it up, and banged in a piton (subsequently cleaned) to get by this section. The final 25 feet were 5.8 and I arrived at a decent ledge with an anchor made out of brand new technical friends. A haul bag was stashed here and fixed lines led up to the summit and down to the headwall. I clipped into the anchor and hauled the bag.

The next pitch is supposedly 5.10d, but it looked relentless and was too thin for hand jams. Hardly wasn't in the mood to try such a vicious crack this close to the top and aided the crack until it leaned back and the climbing became 5.8. He set-up a hanging belay below a roof. Just before I started jugging this pitch, Adam was nearing the belay. "I used to be able to climb 5.8," said Adam as he clipped the belay anchors. This was comforting to hear. I'd been aid climbing for so long I didn't know if I could climb 5.8 any more. You get so used to standing in aiders that free moves seem so foreign and so hard.

The next pitch is really the final pitch of the route. It is only 80 feet long and starts with either 5.11 moves around the roof or about four moves of aid. I aided of course, and then left the aiders behind. I had taken a skeleton rack for this pitch because I knew just about the roof was a 5.9 squeeze section. This section was classic Yosemite. I love this stuff, even while I struggle to thrash up it. I clipped a fixed pin deep in the crack and got a big cam near the top of the squeeze where it pinches down and you have to exit the squeeze over an overhanging bulge. I was near my limit as I placed a cam just above the squeeze and clipped in the rope. Once out of the squeeze altogether, the climbing was perfect hands and I cruised the short distance to the big ledge. We had done it!

As I had exited the squeeze, Scott Burke came rappelling by. The fixed rope and gear were his and he was descending for a quick lap on the Headwall. Scott was working on freeing the whole Salathé route and only had the Headwall to go.

Once again, Hardly took a big pendulum when he unclipped from the pin deep in the squeeze. He came rocketing out of the crack and out into space. This didn't faze him at all and I think he started to enjoy it. Soon he was at the ledge and leading the final 5.6 romp to the top. When I joined him, we shook hands and congratulate ourselves. I think I even hugged him. It wasn't so much of an emotional release since we had been well within ourselves on this route, but it was still quite a thrill to top out on such a big route. On a route we had invested an entire week if you count the drive out here. It was the longest, most difficult route we had ever done. We were thrilled.

While unpacking and re-packing our haul bag, Scott appeared over the edge. Wow! He had descended five pitches down to the Headwall, climbed it, and jugged out in only about 45 minutes. He said it was too cold to take more than one lap on it. Scott Burke proved to be a very friendly guy. "How close are you to freeing the Salathé?" I asked. "Pretty close. I've got 15-20 feet to go on the headwall crack and I've got everything else clean. I've never climbed a 5.13 finger crack before so this is hard for me. The Nose is a face climb - the cruxes anyway. The Salathé is definitely a crack climb." Scott was only the second person to free the Nose (though he didn't do it continuously and he only toproped the Great Roof pitch free) and had just recently led every pitch free on "Free Rider" - a variation of the Salathé that avoids the Headwall. I asked him about the long 5.11a offwidth that is climbed instead of the 5.13a/b endurance crack pitch below the spire. He said that after 23 summers of climbing in Yosemite he was pretty good at climbing offwidths. He goal this summer is to free four major routes on El Cap: Free Rider (done), Salathé (close), Nose in a day, and the Triple Direct. I asked him how confident he was about freeing the Nose in a day since he had never led the roof pitch clean. He responded, "No problem! I TRed that pitch when it was wet and almost redpointed it when it was wet. If it's dry, it will be no problem." I like the confidence. (author's note: four years later he hasn't done any of the three remaining goals).

We left him a gallon of our extra water and some of our empties to dispose of. He thanked us profusely and pointed us in the direction of the descent. I liked the guy. I hefted the surprisingly heavy haulbag. Damn, what was in here? Two sleeping bags and bivy bags, two pairs of climbing shoes, two sets of aiders, two sets of jumars, all the big cams, leftover food, water, the shit tube, cell phone, lots of clothes, helmets, etc. All told it was probably at least 70 pounds. At first this seemed okay - I've carried 70 pounds quite a few times before - but by the time I got down to the car my thighs were totally hammered. It felt like I had done about 3000 squats, which, essentially, I had. Hardly carried the bag for about twenty minutes of the descent but mainly carried the rest of the rack, all the slings, and two ropes.

We had no trouble finding the descent as I had been down it many years ago when I climbed the East Buttress of El Cap. We took a couple of breaks for rest and water. At the four rappels, I would go down first with the haul bag. Hardly put the haul bag on belay and lowered it so that I only need to direct it to the next anchor and secure it. Upon reaching the parking lot, we were met by an elated Judy. We got hugs and cold Root Beers. It was a great reunion.

After some badly needed showers, we told story after story over dinner at Degnan's - the eatery of choice in the Valley. Later we drove to our turn-out of choice and were reunited with the Loobster. More congratulations and more stories. It is such a great feeling to be done with something so long and hard; to be done with the stress and the work; and to share it all with great friends. I loved the route. It has tremendous climbing on it, whether free or aid. Great, committing, scary pitches of free climbing and airy, exciting aid pitches.

The next morning we headed over to Church Bowl for some moderate single pitch climbing. My hands were hammered from the Salathé and I wasn't motivated for anything too challenging. John led Uncle Fanny (5.7) while Judy led Church Bowl Lieback (5.8). Both cruised their routes and Hardly and I followed. The Loobster was strictly an observer. We switched routes and I led Church Bowl Lieback and Judy led Uncle Fanny.

Then, while Hardly led Church Bowl Tree (5.10b), John, Loobster, and I went and climbed all three pitches of Bishop's Terrace (5.8). John led the first pitch (5.7) and Loobster and I simul-seconded the pitch. I led the ultra classic second pitch (5.8). This has to be one of the most perfect cracks in all the world. It just doesn't get any better than this pitch! The Loobster led the final pitch and traversed down the slab to the right to the rappels.

We headed back to the RV for lunch and lethargy. We re-lived the week of climbing. The day Hardly and I were climbing to the Spire, our friends were doing Snake Dike on Half Dome. After this route the Loobster had gone back to work in San Jose and only drove out again last night. Now he was heading back again and we were left to decide what we wanted to do. It was Friday afternoon. We all decided that we were satisfied. We'd done enough climbing.

We left the Valley around 5 p.m. and drove straight through once again to arrive home Saturday afternoon. It had been a great, successful trip with great friends. As I write this a month later, I've just purchased a double portaledge... Now what did Chris McNamara say about Lurking Fear?